A package cannot be considered recyclable if it does not have an end market. In other words, you can’t call something recyclable unless it’s actually getting recycled. How2Recycle has incorporated this concept into its definition of recyclability since the inception of the program in 2012, as directly inspired by Federal Trade Commission guidance:

A product or package should not be marketed as recyclable unless it can be collected, separated, or otherwise recovered from the waste stream through an established recycling program for reuse or use in manufacturing or assembling another item. Federal Trade Commission “Green Guides”, § 260.12 (2012). Emphasis added.

Despite some misconceptions and alternative interpretations of this legal guidance, the Green Guides were truly ahead of their time in 2012 by contemplating this issue of end markets. The How2Recycle program does not call items recyclable if they do not have an end market.

How2Recycle has already made consequential determinations on recyclability because of end markets concerns. For example, How2Recycle downgraded the recyclability of certain plastics in early 2020 based on end market ambiguity. Today, How2Recycle provides greater clarity in this area of recycling that is often misunderstood and rife with nuance and complexity.

For more information on how How2Recycle is designed to comply with Federal Trade Commission and Competition Bureau Canada criteria for recyclability claims, visit How2Recycle’s Guide to Recyclability. To see the prior criteria for end markets for How2Recycle that were in place before this new rule, see the note at the end of this document.

For a summary page of this updated rule, click here.

Assessment criteria to achieve recyclability

As outlined in the Guide to Recyclability, How2Recycle assesses a breadth of information and scientifically credible data related to issue the most appropriate recyclability claim for a specific package. All of the following elements are required to be positively demonstrated in order for How2Recycle to call it recyclable:

- Collection

- Sortation

- Reprocessing

- End markets

A package cannot be considered recyclable if it does not have an end market. While end markets are listed as the final element of recyclability in the above graphic, they can present challenges throughout the recycling process and are not necessarily sequentially ‘last.’ For How2Recycle’s purposes, end markets usually but not always refers to transactions between Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and reprocessors like recycled paper mills and plastic reclaimers. This is because How2Recycle finds those transactions usually the most consequential in determining whether something is actually getting recycled. Still, end market issues can manifest from reprocessor to final end user, or in between collection and the MRF, and so can be understood as an issue that is woven throughout all of recycling.

Accordingly, How2Recycle aims to keep the definition of end markets broad, to mean the stuff actually gets recycled and made into something new again. In practice, this refers to how the value of materials is managed throughout the recycling process, and how that value in turn dictates materials’ fates in recovery.

The How2Recycle program has developed new criteria to assess end markets within the definition of recyclability.

This new rule seeks to bring more meaning and precision to this concept of end markets in a way that (a) increases the accuracy of recyclability claims and (b) also provides feedback to the packaging industry to drive improvements in the recycling system.

This article will explore why end markets have historically been difficult to measure, what How2Recycle’s new rule outlines, and why this rule was designed this way.

Why ‘end markets’ has been challenging to define historically

End markets is the least-developed and understood element of recyclability in the industry currently. Greater clarity and new definitions are needed to communicate recycled material value in a way that is meaningful, constructive and tangible.

The topic of end markets is essentially about value and scale—which makes some aspect of it always subjective and subject to change, especially given that recycling is a global commodities marketplace with little to no regulation. But all materials in society possess varying values and are traded at varying scales at different times for different reasons. The opportunity at hand is to illuminate how we might think about recycled material value in a way that ensures consumers are not deceived but also helps the packaging industry understand how their package is valued for recycling or not, and why.

The packaging and recycling industries (and to some extent the media and certain governmental bodies) often talk about end markets in a binary fashion: either a package “has an end market” or it “doesn’t have an end market.” But when one seeks to apply this yes/no framework to a complex marketplace with ambiguous and layered information, it can be difficult to make this concept meaningful and can sometimes even be misleading. In reality, end markets for recycled materials exist on a spectrum: some packages have very strong end markets, others have very weak ones, and other packages’ values fall somewhere in the middle or are unclear or unknown. The very strong and very weak end markets are known and unmysterious—it’s the grey area in the middle that could really benefit from some additional structure and clarity. What if a package’s value is declining, but still bought and sold at some scale to be recycled into something new again? What if a package is valuable to some recyclers but not all recyclers? What if a package should reasonably be considered valuable to recyclers but that value has not been demonstrated yet with data? These are complex and consequential questions that demand nuanced and contextual frameworks in order to illuminate the appropriate path forward.

Once we acknowledge that end markets exist on a spectrum and different materials possess different values for different reasons, the question then becomes whether—and how—a material of moderate value can be called recyclable. Differing strength end markets may be appropriate for different types of recyclability claims. For example, a qualified recyclability claim telling the consumer the item is not recycled in all communities need not demonstrate the highest level end markets achievable in the recycling industry.

Another important consideration in end markets is that an overly uniform approach across all materials will not work well. Each material is subject to its own unique market dynamics. These dynamics include many factors such as the customer makeup of a certain recycled material and the performance required for certain applications of it; the most widely adopted technologies for recycling certain materials and what level quality feedstock they can handle; and the way the value of one material relates to the value of other materials within the recycling system. Most dynamics play out within a broad material type such as recycled paper mills (but not always), so it may be difficult or inappropriate to compare recycled paper mills’ end markets to say, polypropylene reclaimers’.

Additionally, change and volatility are inherent in recycling. There will always be longer term changes in what gets recycled and how a material’s value influences that over time. But there are also shorter term changes as well—what gets sold in a specific region at a specific price can change regularly. How might we better manage these changes and market dynamics?

How2Recycle’s updated rule to bring greater clarity to the concept of end markets

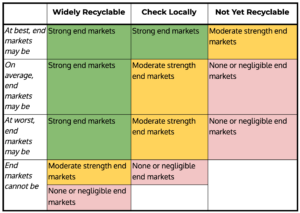

How2Recycle has created three potential end market categories for assessing the end market of a specific package. This is important to move away from a binary yes/no framework to a more meaningful spectrum of value. A package will be characterized as fitting one of the following three categories:

- Strong end markets

- Moderate strength end markets

- None or negligible end markets.

And then based on which end market category applies to a specific package, that package will be eligible for certain recyclability designations:

- Widely Recyclable items must have strong end markets.

- Check Locally items must have at least moderate strength end markets.

- Items that have none or negligible end markets must be deemed Not Yet Recyclable.

In other words, only packages with strong end markets can receive unqualified (Widely Recyclable, Store Drop-Off) recyclability claims.

The definitions of whether a package has strong, moderate, or negligible end markets will be explored in the next section.

How the end market categories are defined

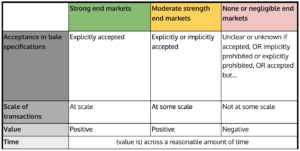

Each definition of end markets focuses on several key elements:

- Demand. Whether the recycling industry has signaled meaningful demand for the material; and

- Scale. Whether the material is getting recycled at meaningful volumes; and

- Value. Whether the material carries meaningful value; and

- Time. Whether value for the material has been sustained over a reasonable time period.

- Strong end markets

- Package is explicitly accepted in an existing bale specification, and that bale is bought by recyclers for recycling at scale, for positive value, for a reasonable amount of time.

-

-

- Explicitly accepted means specifically called out in text of established bale specifications such as ISRI and/or APR model bale specifications.

- Bought by recyclers for recycling at scale means transactions for that bale are:

- Not limited to a subset of eligible recyclers, and

- Occur at relatively high volumes.

- In other words, significant capacity for recycling this material exists, and those recyclers are buying the material at significant volumes.

- For positive value means either the average national price is above $0 or otherwise adequately and intentionally managed by Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and/or governmental entities as part of the overall material mix.

- Reasonable amount of time means at least 2 consecutive years, or

- 1 year with supporting information demonstrating values very unlikely to decrease in forthcoming year

-

- Moderate strength end markets

- Package is explicitly or implicitly accepted in an existing bale specification, and that bale is bought by recyclers for recycling at some scale, for positive value, for a reasonable amount of time.

-

-

- Implicitly accepted means reasonably expected to be included in text and/or intent of established bale specifications such as ISRI and/or APR model bale specifications and known to not cause any bale downgrades at scale if included

- Known to not cause downgrade at scale if included means the majority of recyclers for that material will not meaningfully reduce the price of a bale or reject a bale if that package is included

- Bought and sold at some scale means transactions for that bale:

- May or may not be limited to a subset of eligible recyclers, and

- Occur at moderate volumes.

- In other words, at least moderate capacity for recycling this material exists, and those recyclers are buying the material at at least moderate volumes.

- For positive value means either the average national price is above $0 or otherwise adequately and intentionally managed by Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and/or governmental entities as part of the overall material mix

- Reasonable amount of time means at least 2 consecutive years, or

- 1 year with supporting information demonstrating values very unlikely to decrease in forthcoming year

- Implicitly accepted means reasonably expected to be included in text and/or intent of established bale specifications such as ISRI and/or APR model bale specifications and known to not cause any bale downgrades at scale if included

-

- None or negligible end markets

- Package is unclear or unknown if accepted, or is implicitly prohibited or explicitly prohibited in the existing relevant bale specification, or package is explicitly or implicitly accepted in an existing bale specification but that bale is not bought and sold at some scale, or bale is bought and sold but at negative value for a reasonable amount of time without the material otherwise being intentionally and adequately managed by MRFs and/or governmental entities as a part of the overall material mix.

-

-

- Unclear or unknown if accepted means it’s unclear or unknown if a package description fits into the text and/or intent of current ISRI or APR model bale specifications or if it’s unclear if it causes bale downgrades at scale if included

- Implicitly prohibited or explicitly prohibited means it is known to cause or likely to cause appreciable bale downgrades at scale if included

- Known to cause downgrade at scale if included means the majority of recyclers for that material will reduce the price of a bale or reject a bale if that package is included

- Not bought and sold at some scale means transactions for that bale may be limited to:

- A small to very small subset of eligible recyclers, or

- Low to no volumes.

- In other words, low capacity for recycling this material exists, or recyclers are buying the material at low volumes, or not at all.

- For negative value means either the average national price is below $0 and not otherwise adequately and intentionally managed by Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and/or governmental entities as part of the overall material mix

- Reasonable amount of time means at least 2 consecutive years, or

- 1 year with supporting information demonstrating values very low and/or unlikely to increase in forthcoming year

-

| IMPORTANT: In addition to these end markets categories: if materials are being collected for recycling but are sent to landfill, incineration, or waste to energy to any appreciable degree, those items are not eligible for unqualified (Widely Recyclable or Store Drop-Off) recyclability claims. If this is happening to an extensive degree, an item is not eligible for any recyclability claim at all (will receive the Not Yet Recyclable label). |

Guiding interpretation principles for this rule

On temporary volatility

Recycling is a commodities marketplace, which means that some level of volatility in end markets is not only normal but expected. How2Recycle does not intend for rules to be construed so narrowly that temporary market disruptions need instill panic, nor any ‘restarting of the clock’ to positively demonstrate the ‘value’ or ‘time’ elements. Any disruptions will be assessed in a common sense way through each material’s esoteric lens of historical patterns, future trajectory indications, and level of severity.

On regional volatility

Similarly, regional disruptions are somewhat normal and expected and will be analyzed in a similar way. How2Recycle looks to the national level in all aspects of recyclability, including end markets. In all recycled commodities, it is not expected for reprocessing capacity to be co-located with collection in the same city, state or even region. Recycled commodities cross interstate and international borders regularly, and whether a region can find a market for a material depends on many context-heavy factors such as fuel costs, available nearby capacity, and business contracts. Placing too much importance on any one geographic region’s end markets could be misleading and not representative of the bigger picture of how recycling works. Some materials are reprocessed in many locations but other materials are reprocessed in more specific locations; some materials travel further than other materials to get recycled. Additionally, if How2Recycle were to render a material less recyclable or not recyclable because of the end market challenges of one region, recycling the item in the rest of the country would be unfairly limited and potentially detrimental to the environment. As a result, How2Recycle will zoom out to American and Canadian data in order to identify meaningful patterns in end markets.

On ‘volumes’

Some aspects of this rule are left intentionally open; for example, what constitutes “significant”, “moderate” or “low” volume could be interpreted differently for different materials in different contexts. How2Recycle does not intend for this to be construed as “significant [in the context of all recycled materials].” This is because a material could have a strong end market, but still only constitute a small portion (by weight or volume) of the overall mix of materials that move through MRFs. Nor should it mean “significant [compared to what it used to be][or significant in the eyes of an entity’s aspirations]” or “significant [compared to how much of that material is generated by society overall].”

While our society has profound issues it needs to aggressively face about how materials are valued and managed, How2Recycle refers to ‘recyclable’ as the ability to put something in the recycling bin and then it will get recycled, as opposed to “X% of this material that is made in society ends up going into the recycling system.” Collection, sortation and reprocessing systems still need to grow and improve to a monumental degree so that more valuable materials can be captured and used again. Since investment in those areas often requires good ‘end markets’ first, hopefully this rule provides industry with some constructive ideas for how they might go about achieving their recovery goals.

On ‘capacity’

If there are recyclers (such as PET reclaimers) who are willing and able to actually recycle a material, and even have the infrastructure to prove it (to prove “reprocessing capacity”)—that does not automatically mean that there is demand at scale. Sometimes there can be structural hurdles for a recycler to actually get the material. For example, maybe there is a bottleneck in collection because too few Americans have good access to recycling—so even though the recycler wants it, they aren’t getting a lot of it. Sortation capacity can limit what gets recycled at scale—if MRFs do not have the physical space or necessary equipment to sort, store and sell a certain material, then that can be an important limiting factor. The rule is intended to only ‘count’ what volumes of material are actually getting to the recycler and getting recycled.

On ‘bought… for recycling’

There may be instances where a recycler such as a recycled paper mill or a reclaimer buys a bale of material, but doesn’t actually intend to recycle all of the materials typically found in that bale. Perhaps the material is intentionally sorted out before being placed in the reprocessing equipment, or habitually removed from the rest of the material during the recycling process. The rule is intended to only ‘count’ the stuff that’s bought that actually gets recycled. Due to the complex dynamics of certain bale specifications and how they are bought and sold, and how that interplays with different recyclers’ processing technologies and market niche, whether a package within a bale will get recycled may be a context-specific assessment and additional information may be required to demonstrate end markets.

On ‘otherwise… managed’ value

This rule intentionally uses the word “value” instead of “price” because price is only one way to assess value. It’s typically the most prominent and important because recycling is a capitalistic marketplace, but there are other dynamics in the recycling system that enable a material to get recycled despite its challenged (and sometimes even negative) dollar value. For example, glass has been traded at a loss in many places for many years, and still gets recycled. Whether or not materials possess value is due to a variety of factors including its role in the overall mix of materials at a MRF and how the MRF manages its profitability relative to contracts with municipalities, tipping fees, sort costs, volumes, and other variables. Additionally, potential future Extended Producer Responsibility regimes or other governmental initiatives could directly influence whether a material is valued, and in turn, recycled.

On what exactly gets run through the formula

This end markets analysis will take place on a package by package basis. How2Recycle will not run a bale spec through the process, but rather a specific package format. For example, How2Recycle will not run the 3-7 bale through the formula, but rather, polypropylene tubs (which are sometimes, but not always, present in the 3-7 bale). More granular packaging specifications such as attachments, barriers or coatings will likely but not always be analyzed in the sortation and reprocessing elements of recyclability separately. There could be some overlap with end markets on these sorts of details and those will be assessed on a case by case basis as needed; focus will be placed on what level of granularity may be meaningful in recyclers’ transactions.

On uncertainty & common sense

In the presence of uncertainty as to how a package should be characterized in terms of end markets, How2Recycle will err on the side of conservative and not issue a claim or issue a qualified claim.

This rule is intended to be applied in a common sense way, where all the relevant and available information will be considered in context. The rule is subject to change and improvement, especially as How2Recycle will apply this rule to divergent and complex sets of facts into the future. Accordingly, exceptions or greater nuance could apply to certain package types under specific compelling or changing circumstances. For more detail on what quality data How2Recycle finds scientifically credible, visit the How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability.

Why How2Recycle designed the end market rule in this way

On consumer perception

First and foremost, How2Recycle seeks to prevent consumer deception and greenwashing in the realm of recyclability claims. Given the complexity in the area of end markets and the increased (and sometimes incorrect or misleading) attention given to it, it became critical to make this aspect of recyclability clearer. To that end, How2Recycle sought feedback from the Federal Trade Commission on this updated criteria, and the rule was adjusted as a direct result of that feedback. Additionally, the How2Recycle Advisory Committee provided feedback and their recommendations are reflected in the rule. Future consumer perception testing could influence how this rule is revised in the future.

Lack of recycler information is a barrier to better end markets measurement

One might be tempted to ask, “well can’t you just track exactly how much of each material is getting recycled annually, and make sure that’s equivalent to the exact amount that’s getting collected for recycling annually?” Well, in 2021, no. Recycling is not a super transparent supply chain. There are many barriers to better measurement: there is not a universally adopted and timely mechanism to measure collection and reprocessing on a national scale with a relatively high degree of granularity or accuracy. Recycler confidentiality is a huge part of this: recyclers’ business models make them unwilling and sometimes unable to disclose their customers, volumes traded, bale spec details, locations of sales, and amounts and makeup of residual. Decisionmaking on these factors can be decentralized or only available in inconsistent reporting formats. Some materials are traded through brokers, adding another layer of transactions. Additionally, recyclers are often in competition with one another, making anecdotal information sometimes unreliable; some recyclers have a financial interest in the recycling stream being a certain way, and so may be encouraged to deliver information in a certain way. If recyclers would be willing or able to share a little more information, measurement of end markets could be improved. But the general public and packaging industries would also be well-advised to understand the inherent characteristics and limitations of the recycling marketplace. It’s mostly a private business, even though many consider it, or want it to be, a public utility.

On limitations of how ‘demand’ is measured

Demand is hard to identify and measure because it can be so subjective, anecdotal or context-dependent. What is ‘enough’ demand? How much demand is needed for a new or innovative material before it snowballs and becomes a successfully recycled material? Does the demand need to be actual, or is speculative demand meaningful? ‘Who’ is the arbiter on whether demand exists? One can always find divergent responses to any of those questions. In the presence of imperfect and too little information on market demand, established bale specifications such as ISRI and/or APR model bale specifications appear to be the best available way to assess this today (so long as they are analyzed alongside other elements of end markets: scale, value and time). That said, they are only a partial snapshot of demand. Model bale specs are a signal of demand—a credible and representative group of recyclers has indicated a willingness to trade, and has outlined what that should look like. But, those model bale specs are still just an example of what a real bale spec could look like—recyclers may adjust the specs as needed for their own business. Some bale specs are more mature than others (and thus better understood and defined) and some bale specs are more popularly used by recyclers in real life than others. Observers should note that the development of new model bale specs or adjustment of existing ones can at times be a highly political process, subject to its own set of complex and competing forces and interests.

On limitations of how ‘value’ is measured

For average national pricing information, How2Recycle references recyclingmarkets.net. But like bale specifications, this does not provide a complete or perfectly representative picture of how material value is assessed and managed. Databases like these do not provide mechanisms to understand how certain prices or price changes impact buy/sell behavior, and in what ways. Still, this particular database is a credible independently-operated tool where prices are reported on a weekly basis by consumers of that recycled material (end users/processors) as well as MRFs and haulers. And as explored earlier, there are challenges in assessing value beyond mere pricing of a material in isolation; this is why the end markets rule contains an exception for ‘otherwise intentionally and adequately managed value’.

Why do 1-2 years constitute a reasonable amount of time?

Especially in light of dramatic export restrictions playing out in the last few years, How2Recycle has observed that market volatility does tend to shake out on the years’ timeframe; weekly, monthly or quarterly volatility does not provide a sufficiently zoomed out picture for purposes of recyclability labeling. Not only would it be confusing to consumers if recycling labels changed on a semi annual basis, it is also totally impractical from a brand perspective to adjust artwork on this small a timeframe. At the same time, if the timeframe is too long, there is a risk of potential consumer deception if a material is experiencing a downward trajectory, and more than two years may be an unreasonably long time to wait for an innovative or emergent material to achieve a recyclability claim if it is achieving success. How2Recycle was also inspired by the well-crafted two year language included in Maine House Bill 2104 (2020).

On the elephant in the room: virgin prices

One essential factor that contributes to the value of recycled material and its viability as a manufacturing feedstock into the future is the price of its virgin counterpart. This is hands down one of the most powerful influences on the end markets of recycled material (explored further in Sustainable Packaging Coalition’s Design for Recycled Content Guide) and presents a significant challenge to the circular economy—particularly for plastics. This is a complicated market issue that is beyond the scope of How2Recycle’s current ability to measure or manage in any meaningful way.

Another key factor that impacts material value is landfill tipping fees. In some localities, it is extremely inexpensive to landfill materials, so there is a much greater incentive to not recycle. In contrast, some areas with high tipping fees have much healthier end markets.

While not all of these factors are reflected in the text of the rule, they can provide helpful context to packaging producers who are interested in maintaining the recyclability of their material. Additionally, as the recycling industry evolves and more and better information becomes available, How2Recycle may be able to incorporate some of these elements into future iterations of the end markets rule.

A note of caution for packaging producers

Just because an item is characterized as having strong end markets in order to substantiate a recyclability claim, that does not mean it’s necessarily strong in other important ways. For example, it may not be as strong in the context of whether it will be recycled by society long term, or it may not be as strong as it arguably should or could be. How2Recycle looks at the recycling system of today to issue labels, but many companies’ goals are dependent on the recycling system of the future. Similar to how How2Recycle’s recyclability feedback to brands exceeds the information in the label, companies should not stop learning or improving based on the on-pack label their package receives. Individual companies and trade associations representing certain packaging types should very seriously assess the end markets for their materials and actively develop and fund initiatives to sustain and grow those end markets. Talk is insufficient; action is required. The push to support recycling of a material often must be continuous—if efforts cease, there is risk that the recyclability claim may only be valid for a temporary period of time. Some materials require timely, active support in order for recyclability to be maintained; others may require later intervention if certain conditions come into play. The degree of risk depends on many factors such as history, diversity of recyclers and end markets, or evolving supply. No one should ever assume that just because an item has an unqualified recyclability label that it is “safe” or more or less stable. Two items may both be characterized as having strong end markets, but one could just barely exceed the standard whereas the other may be the most valuable material in the entire recycling system with no real threat of diminished value in the foreseeable future. End markets are serious business (literally), and companies who are serious about recyclability goals should put building them at the front of their strategies.

How2Recycle strives for continuous improvement and learning. Any interested parties are encouraged to provide written feedback on this rule and how it can continue to evolve into the future to how2recycle@greenblue.org.

Companion resources:

How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability

How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability

For historical reference, this is How2Recycle’s prior criteria for assessing end markets:

There is no straightforward, easy way to assess end markets across all materials in a standardized way. As a result, How2Recycle currently looks at a variety of considerations based on the circumstances, including but not limited to:

— Secondary material pricing at recyclingmarkets.net

— Inclusion of package type in industry model bale specifications such as APR Model Bale Specs, ISRI Scrap Specifications Circular

— Aggregated expert or media reported information regarding landfilling or incineration post-collection

— Aggregated expert or media reported information regarding buy/sell transactional behavior at the MRF or recycler levels

— Feedback from individual recyclers or trade associations representing recyclers on value of specific pack types

— Specific research available or published by consultancies or other organizations regarding end markets for certain materials.