The purpose of this Future Guide is to transparently provide How2Recycle member companies with guidance about how to build a future case for their packaging to be considered recyclable, and also may give members of the general public insight into the complexity of packaging recyclability and the recycling system today.

Contents of this Future Guide

-

‘Core’ versus ‘recyclability-challenged’ packaging explained

-

Assessment criteria to achieve future recyclability

-

Considerations for far future recyclability

-

Considerations for substantiation data

-

Recommendations for strategizing future recyclability

-

Steps for How2Recycle members to achieve future recyclability

This Future Guide builds on the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability, available here. If you haven’t read it yet, we suggest you start there first.

What is this Future Guide and what is it for?

The purpose of this How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability (‘Future Guide’) is to transparently provide How2Recycle member companies with guidance about how to build a future case for their packaging to be considered recyclable, especially as it relates to receiving certain How2Recycle labels. Additionally, labeling changes may be challenging for members, so this Future Guide will help companies understand why materials are experiencing change in the recycling system. It also may give members of the general public insight into the complexity of packaging recyclability and the recycling system today.

This Future Guide will describe how we conceptualize the future of recyclability-challenged packaging, what to keep in mind and expect if you are a How2Recycle member that wants your challenged packaging to be recyclable, and what specific data or changes may be required for your challenged packaging to be considered recyclable under the How2Recycle program.

‘Core’ versus ‘recyclability-challenged’ packaging explained

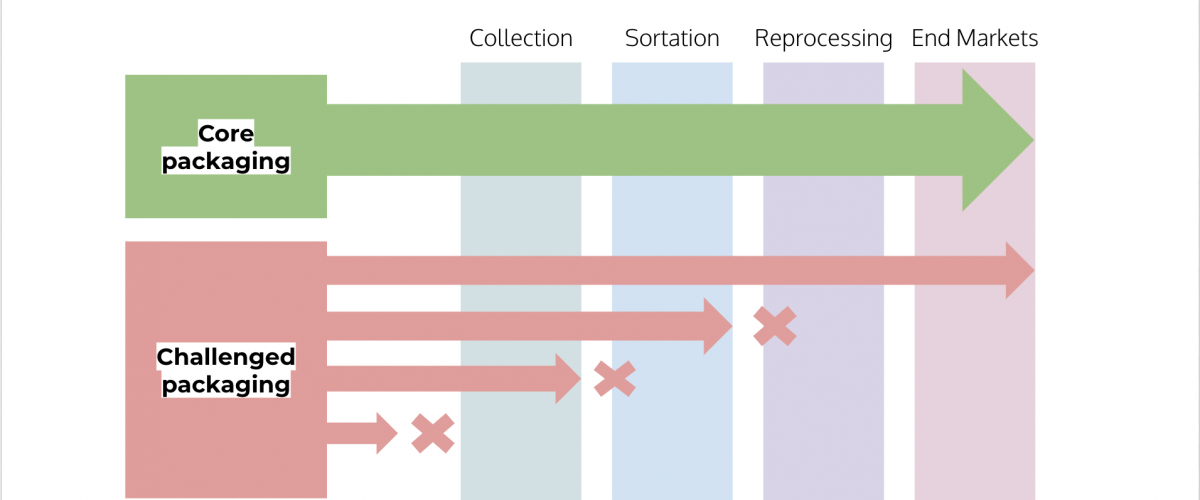

Some packages aren’t recyclable today (See the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability for a definition of what recyclable means). Some may be recyclable today, but there is little or no data available to substantiate a recyclability claim for that item. To help guide conversation around these concepts, How2Recycle has developed terminology to help distinguish between the classic packaging types that are widely recyclable today from those packaging types that the recycling system is not currently designed to specifically capture or for which data does not yet exist to substantiate a claim: core packaging vs. recyclability-challenged packaging.

Core packages are well suited to recycling today because the existing recycling system was developed specifically to accommodate these traditional packages. They are not challenged in collection, sortation, reprocessing, or end markets. There is no doubt about whether these items are collected at scale, sorted correctly in a Material Recovery Facility (MRF)* into a high-value bale, and enjoy strong demand from recyclers to be manufactured into another item. A significant amount of data exists to easily substantiate Widely Recyclable claims for these items.

Examples of current core packaging:

-

- Corrugated boxes (aka ‘cardboard’ boxes)

- Uncoated or clay coated paperboard without direct food contact (like cereal boxes)

- Steel cans (like soup cans)

- Aluminum cans (like beverage cans)

- Transparent clear, transparent blue or transparent green PET bottles (like beverage bottles)

- HDPE bottles (like laundry detergent)

*A fair amount of core packages are collected and recycled through a source-separated system (like bottle deposit collection, source-separated drop-offs, and dual stream curbside collection), and so never see a MRF.

In contrast, recyclability-challenged (‘challenged’) packages are those that either face a more challenging journey to actually being recycled, or those that face a more challenging journey to receive a recyclability claim due to lack of sufficient substantiation data.

Examples of current recyclability-challenged packaging:

-

- Tubes (toothpaste, lotion)

- Hot paper cups (coffee)

- Cold paper cups (fountain drink)

- Ice cream paper packaging

- Fiber foodservice packaging with direct food contact

- Alternative fiber packaging (e.g. bagasse, bamboo)

- Coated flexible papers

- Certain polyethylene (PE) film innovations

- Composite metal-bottom canisters

- Expanded polyethylene (EPE) protective packaging

- Multimaterial flexible packaging

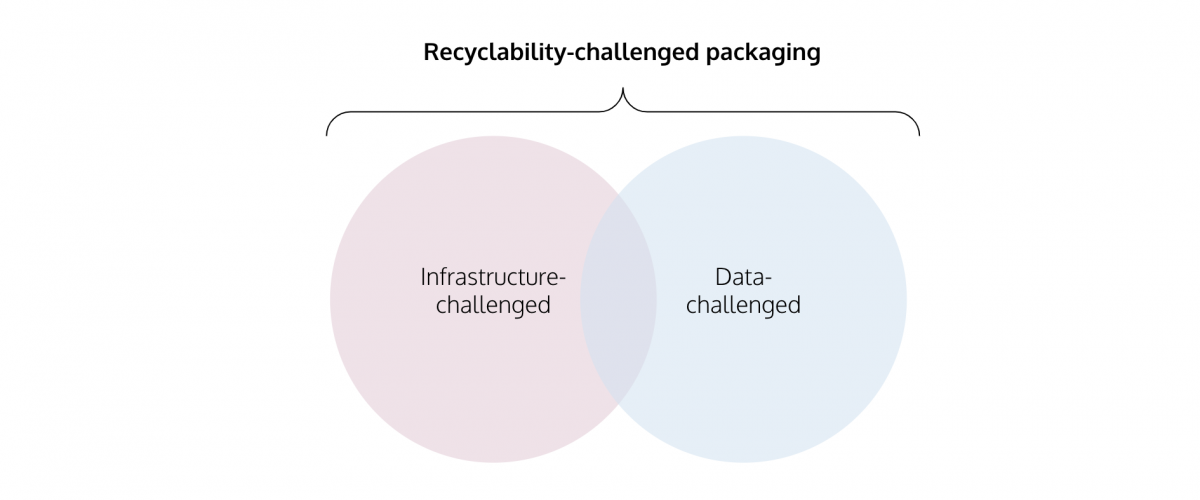

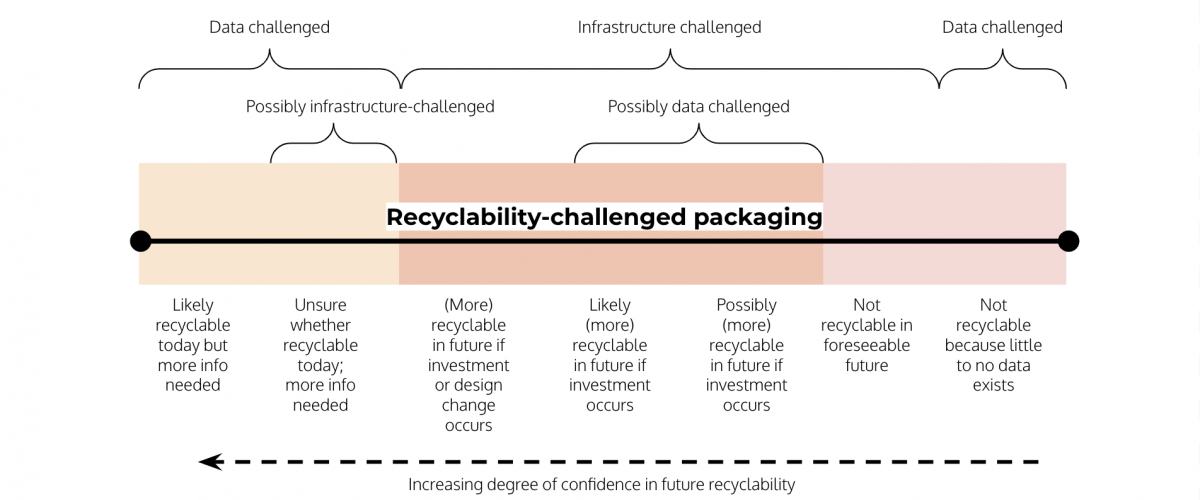

There are two main types of recyclability-challenged packages: infrastructure-challenged packages, and data-challenged packages.

Infrastructure-challenged packages are those where the recycling system was not specifically designed to capture them (yet) and are known to face substantial challenges in collection, sortation, reprocessing, and/or end markets. Some infrastructure-challenged packages may not feasibly become recyclable in the foreseeable future, for reasons like viability: they are too expensive to reprocess. Other infrastructure-challenged items could become more recyclable, relatively easily, if the appropriate investments are made in infrastructure.

Data-challenged items may be those where the system wasn’t specifically designed with them in mind, but they may still get recycled if a consumer places the item in their bin—but no company or organization has yet demonstrated with data that a recyclability claim can be made. Accordingly, How2Recycle cannot give a member the label that may be desired.

Some packages may be challenged in both infrastructure and data to substantiate a recyclability claim. But what all recyclability-challenged packages have in common is they sit on the other side of the spectrum of packaging recyclability from core packages—“on the fringe” of the recycling system.

Note that some recyclability-challenged packages may have strong sustainability attributes in other respects, like sustainable sourcing, design optimization, or material health. Remember that end-of-life considerations are only one aspect of sustainable packaging.

Here is another way of looking at the differences between core and challenged packaging:

Not all recyclability-challenged packaging is equal.

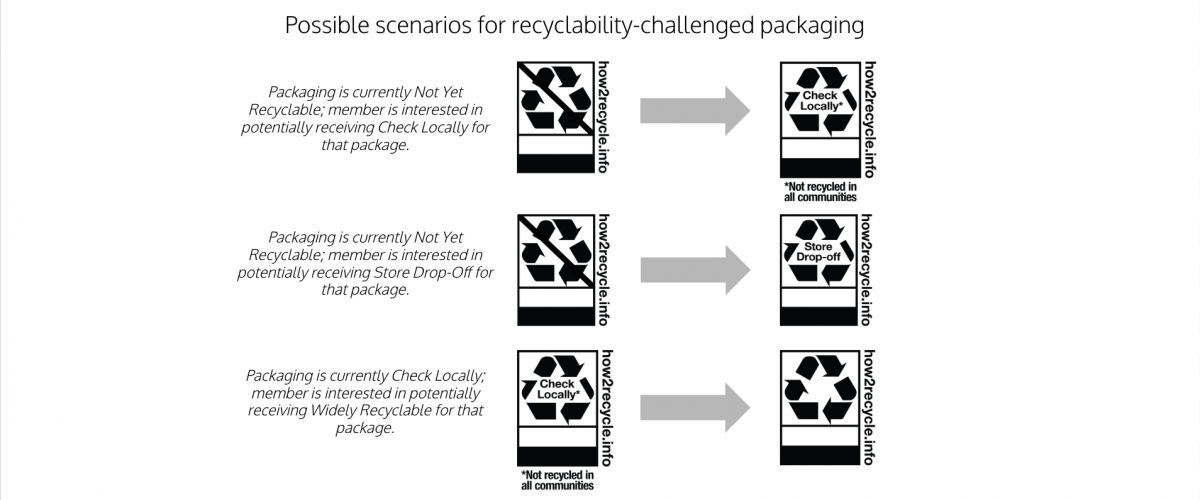

Most challenged packages are currently designated Not Yet Recyclable in the How2Recycle program, but some packaging might be somewhat recyclable today (“Check Locally”) with the goal of achieving a Widely Recyclable designation. This is all to say: not all challenged packaging is created equal.

Here are a few guiding principles to put challenged packaging in context:

- Different journeys. Because of the complexity of the recycling system, some challenged packages may have different solutions to becoming recyclable compared to other challenged packages.

- Different timetables. Some packaging may have the same or a similar route as another challenged package but has a longer way to go than the other one to be considered recyclable.

Types of challenged packaging

Based on these considerations, packages may be roughly placed in one of these categories of challenged packaging:

- Data-challenged.

- Likely recyclable today but more data needed. Current recycling systems likely support the recycling of this item at scale, but more substantiation data is required to support a recyclability claim. More data may be needed in one, some, or all of the following elements to support a more positive recyclability claim:

- Collection

- Sortation

- Reprocessing

- End markets

- Not recyclable because no to very little data exists. It may be unclear which above category a package might fit into because little to no data exists to help plot its current and potential future position in the recycling system.

- Unsure whether recyclable today; more information needed. Current recycling systems may or may not support the recycling of this item at scale. If so, more substantiation data is required to support a recyclability claim. More data is needed in one, some, or all of the following elements to support a more positive recyclability claim:

- Collection

- Sortation

- Reprocessing

- End markets

- Note that if the data is gathered but cannot ultimately support a recyclability claim, the package would fall into the infrastructure-challenged category outlined below.

- Likely recyclable today but more data needed. Current recycling systems likely support the recycling of this item at scale, but more substantiation data is required to support a recyclability claim. More data may be needed in one, some, or all of the following elements to support a more positive recyclability claim:

- Infrastructure-challenged.

- (More) recyclable, likely recyclable or possibly recyclable in future if infrastructure investment occurs. Because of a developed body of data, we know confidently or somewhat confidently that the current recycling system cannot support the recycling of this item today, but investments in the recycling system will or could possibly change that (likelihood of future success varies). Additionally, changes in packaging design may also be necessary under the circumstances (see next bullet point). Investments may be required in:

- Collection. For example by increasing the amount of communities that accept that item, or increasing the clarity of community instructions to demonstrate the item is accepted.

- Sortation. For example by installing more commercialized sortation equipment, updating existing sortation equipment (either via software updates or retrofits) to enable better sortation, adjusting MRF processes like pick line worker training, or inventing novel ways to sort materials at MRFs at scale.

- Reprocessing. For example by installing more commercialized reprocessing technologies at recyclers, or inventing novel ways to reprocess materials at scale.

- Note that chemical recycling (a reprocessing technology) reaching scale could be a game changer for certain challenged plastic packages.

- End markets. For example by creating a new bale specification to encourage more MRFs to bale these items, or going city-by-city to connect sellers with new buyers of the material, or inventing new applications for the material that would support demand at scale.

- (More) recyclable, likely recyclable or possibly recyclable in future if packaging design changes. The best way for packaging to become more recyclable is simply for its design to change to fit the existing recycling system. Because of a developed body of data, we know confidently that the current recycling system cannot support or is not optimized to support the recycling of this package today, but changes in packaging design will or could possibly change that (likelihood of future potential success varies). Additionally, investments in infrastructure (see prior bullet point) may also be warranted under the circumstances. Packaging designs may be required to better enable:

- Sortation. For example, by changing the label on a plastic container to enable it to be better sorted by near infrared (NIR) sorting equipment.

- Reprocessing. For example, by switching to pressure sensitive labels where the label substrate, adhesive and ink meet criteria for Preferred in the APR Design Guide.

- End markets. For example, by adjusting resin color to one with stronger market demand.

- Note that on the How2Recycle Member Platform, members already receive specific recommendations for packaging design improvement to make their packaging more recyclable.

- Not likely recyclable in the foreseeable future. We know confidently that the current recycling system cannot support the recycling of this item today, and potential for investments or changes in the recycling system are unknown or unlikely. Or, the package is fundamentally not designed for recyclability (for example, poor yield ratio), or is an active disruptor in the current recycling system, or exists in such a small concentration and is novel enough that it doesn’t fit into other existing package types that gathering momentum around its recyclability is unlikely. See later section about ‘far future recyclability’ for more insight.

- (More) recyclable, likely recyclable or possibly recyclable in future if infrastructure investment occurs. Because of a developed body of data, we know confidently or somewhat confidently that the current recycling system cannot support the recycling of this item today, but investments in the recycling system will or could possibly change that (likelihood of future success varies). Additionally, changes in packaging design may also be necessary under the circumstances (see next bullet point). Investments may be required in:

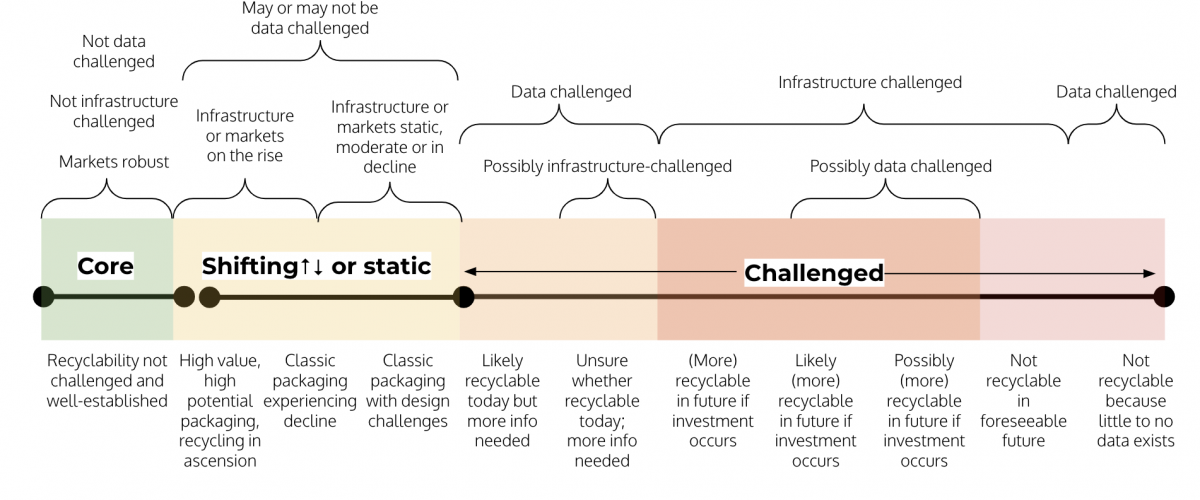

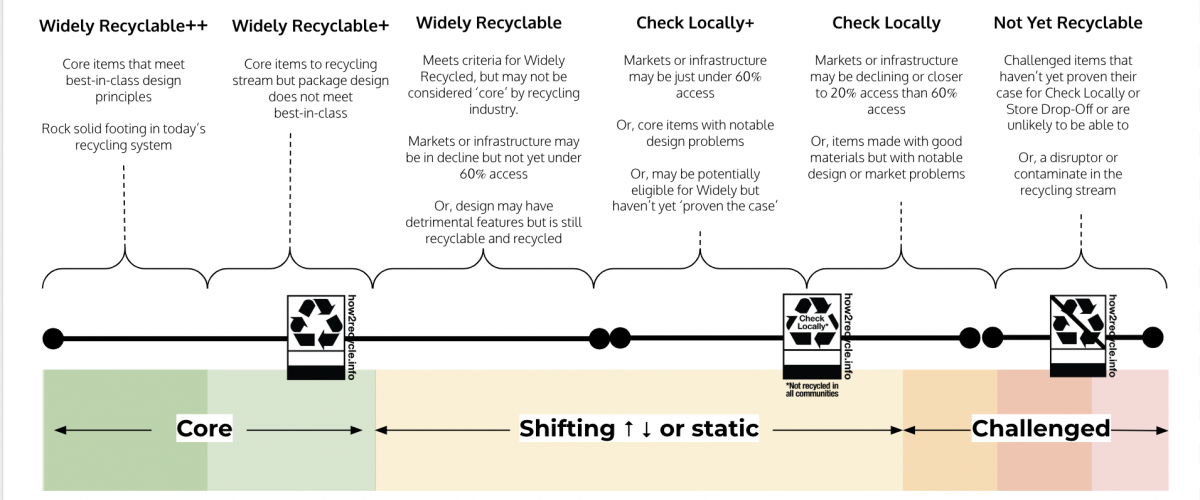

Note that ‘core’ versus ‘challenged’ is a binary (and thus limited), informal concept to help tease out issues as to how and why not all materials flow through the recycling system similarly. There are some items that are debatable as to whether they would more likely be classified as core or challenged. There is a spectrum of the recyclability of packaging, and clear categorizations may not exist for all materials. Some may fall between core and challenged. Those may be items with:

- Shifting recyclability – on the rise. Either the markets or the infrastructure (or both) for these items are stronger than they were in the recent past, and may currently feature Widely Recyclable or Check Locally. These items may or may not be data-challenged.

- Shifting recyclability – on the decline. Either the markets or the infrastructure (or both) for these items may not be as strong as they once were. These items may or may not be data-challenged.

- Static recyclability. The infrastructure for these items, or their markets, may be static and holding at a moderate level. Any recyclability changes over time (within the last few years) may be negligible. The recyclability of these items is more stable than challenged items but not as stable as core items. These items may or may not be data-challenged.

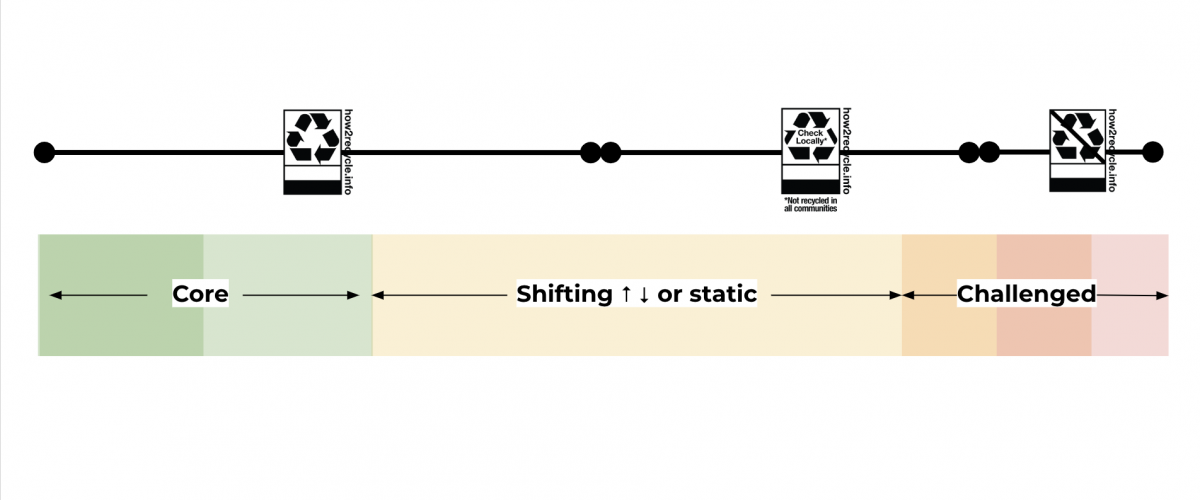

The informal concept of ‘core’ and ‘challenged’ does not directly correlate to the 4 recyclability categories for How2Recycle. That’s because the How2Recycle label on-package only conveys a specific piece of information: whether, from a legal perspective, one can currently claim it’s recyclable to the consumer. How a package has historically fared, is faring and will fare in the recycling system, and how the package design could be improved for recyclers (recyclability claims aside)—these are more nuanced considerations.

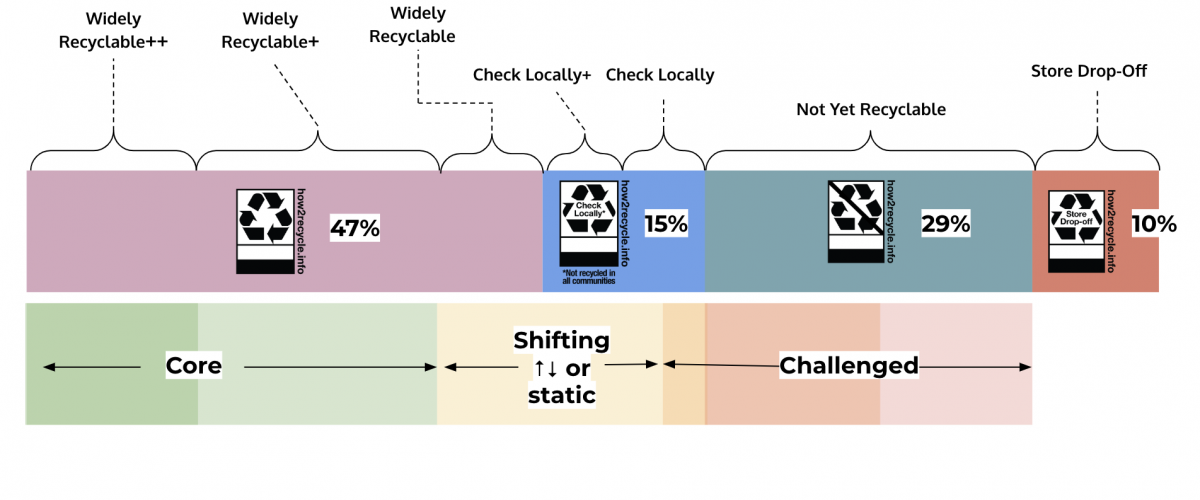

Not all packages with the Widely Recyclable label enjoy the same stability and viability as other packages with the Widely Recyclable label. One might categorize some Check Locally packages as challenged, but other Check Locally packages may be in the shifting or static categories. And Store Drop-Off is an interesting case because some might consider PE film core and some might not, but within PE films, there are challenged designs. This is how we tend to think about the overlap of these concepts:

Widely Recyclable items could be core or shifting; Check Locally items could be shifting, static, or challenged; and Not Yet Recyclable items are always challenged.

To provide further subclassification about how some packages may be better positioned within their broader recyclability category, consider this concept of recyclability “+” or “++”:

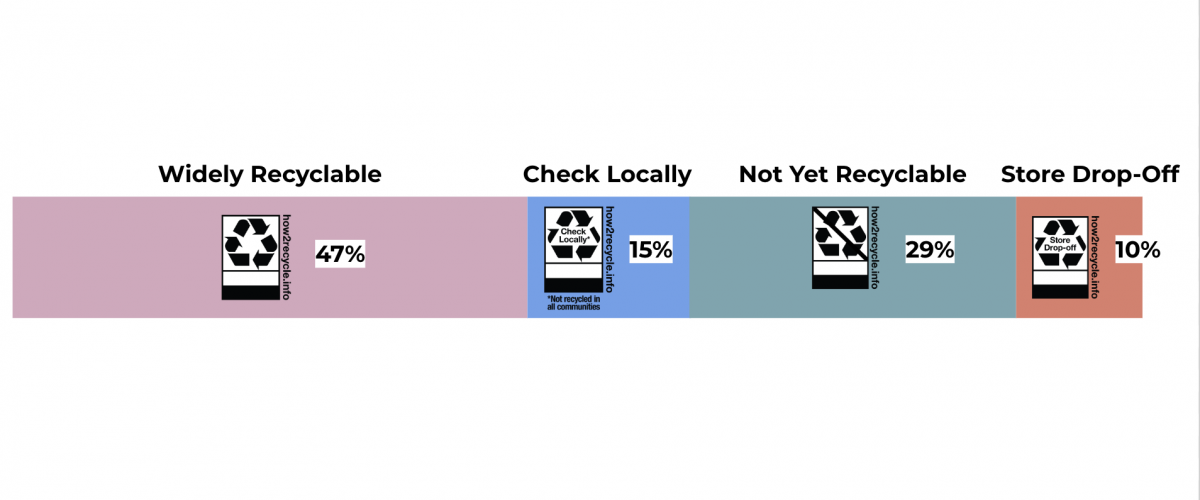

This isn’t to say that there are equal amounts of these types of packages in the marketplace—equal focus should not be placed on all categories. Recyclability-challenged packaging arguably does not deserve the majority of our attention and energies as a community. Of the nearly 100,000 How2Recycle labels in the marketplace, most are Widely Recyclable or Not Yet Recyclable:

Putting the concepts together of core and challenged on top of the prevalence of the labels in the marketplace, you can see there are different “sizes” of opportunities and challenges for the different categories of recyclability:

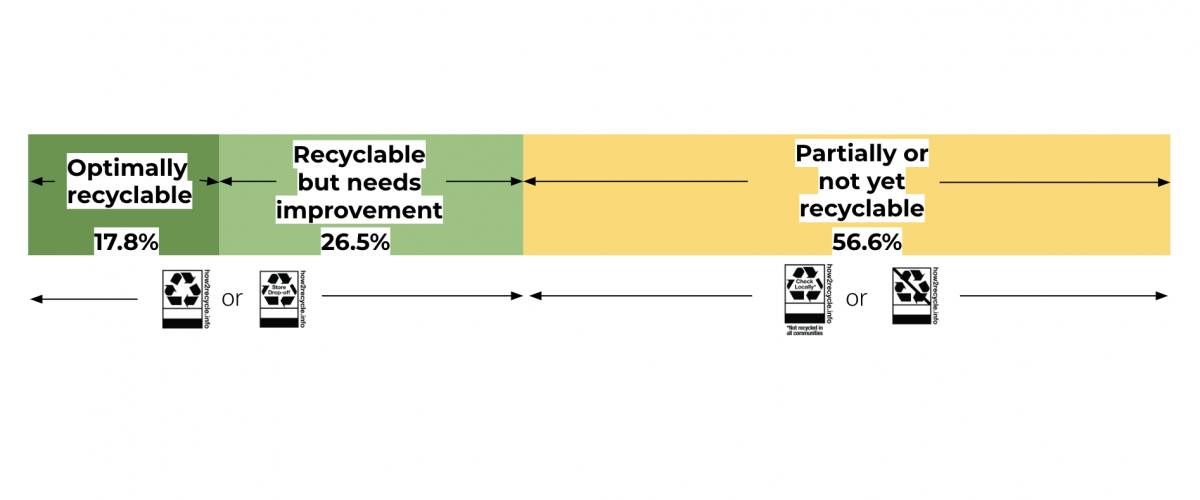

And how does this stack up against the overall recyclability categories (colors) that How2Recycle issues members for each overall package design on the How2Recycle Member Platform? These categories are designed to help our members track their progress against their recyclability goals, and inform members about when their package design needs improvement or is best-in-class.

For all How2Recycle member packaging, the graphic shows that 17.8% are designated optimally recyclable, 26.5% are recyclable but need improvement, and 56.6% are partially or not yet recyclable. The ‘green’ categories may be either packages where all main components are Widely Recyclable or Store Drop-Off, and the yellow category is where at least one main packaging component is Check Locally or Not Yet Recyclable.

These infographics demonstrate that there are many different ways How2Recycle seeks to empower its members to assess the success of packaging in recycling.

Assessment criteria to achieve future recyclability

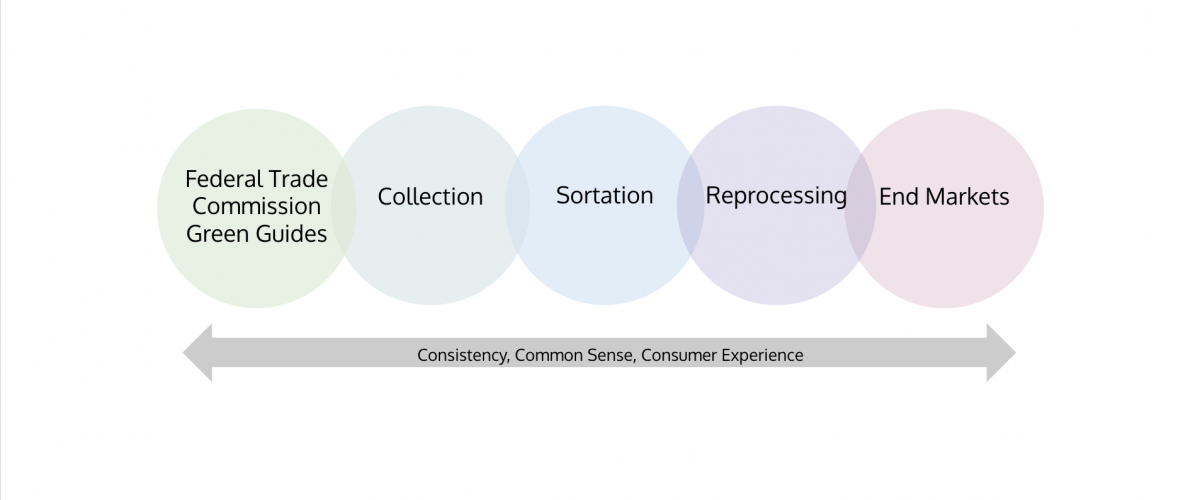

In the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability, How2Recycle explains how scientifically credible data is required to support four assessment criteria in order to call something recyclable:

- Collection

- Sortation

- Reprocessing

- End markets

The below table reflects important assessment criteria under each element of recyclability but adds how it may specifically relate to future recyclability. But first, some important caveats to the below criteria:

- Not comprehensive. This guidance is not all encompassing. In other words, do not rely on the guidance here as complete for a package. Guidance may contain nuances depending on your packaging type and new data may illuminate the need for more details. Some packages have questions not listed here (too complex to include all and too many changes over time). This is intended as general guidance to cover most packages.

- Subject to change. Our guidance and standards are subject to change at any time, and a How2Recycle label may be rescinded at any time based on new data or standards. This is because the recycling system continuously evolves, and How2Recycle’s data about recyclability updates continuously. That said, broad changes to recyclability (for example, if all HDPE tubes were to qualify for the Check Locally label) will be communicated to all How2Recycle members simultaneously via updates to the Guidelines for Use on either January 31 or July 31 of each year via email newsletter, as well as posted to how2recycle.info for the general public (starting January 2020).

- Not one-size-fits-all. Not all criteria listed under each element apply to all packages. It depends on the specific package and all the circumstances at play. While we will issue How2Recycle members a custom label based on all the criteria under the circumstances for that package today (see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability), we are unable to give members a mathematical formula or affirmative promises on a specific checklist for you to legally be able to rely on for future recyclability. However, the below table is designed to present the important questions to empower you to understand and dig into these issues yourself, and why we are unable to give a formula.

- Embrace the grey. This Future Guide contains intentionally open-ended questions that seek to tease out ambiguous, unclear or complicated issues, so a yes or no answer, or a clear one, or a quantifiable one may not be possible (at least not right now). The recycling system is evolving, and our community’s knowledge and set of tools around recyclability become more sophisticated over time. All these considerations mean we are carving out new territory, where black and white does not exist. As we broaden participation in recycling and the How2Recycle community, establish new and improved feedback loops, and continue to foster complex adaptive systems thinking, the interconnected picture of recycling will become bigger, and clearer, and will likely shift. There may be journeys to recyclability that are not even contemplated in this Future Guide. Critical thinking and creativity go a long ways here. There are no perfect or single answers or solutions, and there is no silver bullet.

Note that this table is also in the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability, but includes additional detail about the grey areas under each element of recyclability that may be especially relevant to building a future case for recyclability.

| Element | Assessment criteria |

| Collection

(Access to recycling) |

For the standards for access to support a Widely Recyclable or Check Locally claim, see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability. Those standards still apply here. However, in this Future Guide, since we are focusing on less-recyclable packaging, or packaging where it’s unclear if it’s recyclable today, here are some additional layers of consideration for access analysis: _________For packages where the SPC Centralized Availability of Recycling Study may not give a precise answerSee this article. ________ For data that a member has collected If a member has commissioned its own study to supplement or update the SPC Centralized Availability of Recycling Study, some considerations may include: Is the data nationally representative? If so, how? Why was this sample size chosen? Is the methodology the same, or similar to the SPC Centralized Availability of Recycling Study, or better? If not similar, the member must present compelling reasons why this is sufficient or comparable in credibility, accuracy and completeness. Is this data timely—in particular, does it take into account changes in the recycling system due to current export conditions? Was the data collected by an objective, qualified third party to yield accurate, reliable results? See later sections in this Future Guide for more detail on substantiating data and what the data needs to look like. For a more detailed discussion of what ‘explicit’ or ‘implicit’ access means, and what we find a compelling methodology to be, see the 2021 SPC Centralized Availability of Recycling Study. |

| Sortation | For the criteria for sortation to support a Widely Recyclable or Check Locally claim, see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability. Those criteria still apply here. However, in this Future Guide, since we are focusing on less-recyclable packaging, or packaging where it’s unclear if it’s recyclable today, here are some additional layers of consideration for assessing sortation:

______ For packages where it’s unclear if it will be sorted correctly in MRFs Is there evidence that the item will get correctly sorted at MRFs even though MRF operations were not designed specifically for the item? Was a MRF not designed to specifically sort it, but scientifically credible data indicates that the item will be sorted successfully by the relevant sorting technologies, including screens, 2D/3D, NIR, eddy current, magnets or robotics, in the form in which it would arrive at the MRF (somewhat compressed)? Note that not all sortation technologies are relevant for all packages. Is there a possibility that hand pickers at a MRF would pull this item out of the stream? Are they trained to? Is there a possibility that the presence or absence of certain equipment, or certain equipment settings may impact the success of sorting? How might you account for sortation of this item by AI and robotics? Will it be visually recognized? Is it an item of priority for robotics sorting at the majority of MRFs using robotics? In this sense, will it be positively sorted or would it be pulled out by robotics as a contaminant? This is not yet a criterion for How2Recycle, but will be. For emergent materials, AI and robotics may present either a challenge or an opportunity, depending on the package type. Its place in the bale Do model or industry bale specifications (such as ISRI’s or APR’s) explicitly allow or prohibit this item? Or are they silent, ambiguous or unclear? Will the presence of the package in a bale potentially cause that bale to be downgraded, per industry specs? Its relationship with other materials in the mix Would this item contaminate other streams by being sorted to the wrong material bale? If so, does that substantially differ from the success rate of similar classic items of that same material or format? Relationship between consumer behavior and successful sorting Substantiating data Generally, there are two types of approaches to this sort of data: lab testing, or field testing. There are arguments about the pros and cons of those two approaches. We ask members who are interested in collecting their own data because a sortation test protocol may not exist or may not answer the specific concern (see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability for detail) to propose a methodology for testing that they believe would be scientifically credible. More on that later in this Future Guide. Note that How2Recycle is currently studying 2D/3D sortation for certain plastic and paper items. Assessment is taking place on a case-by-case basis for items in the grey. |

| Reprocessing | For the criteria for reprocessing to support a Widely Recyclable or Check Locally claim, see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability. Those criteria still apply here. However, in this Future Guide, since we are focusing on less-recyclable packaging, or packaging where it’s unclear if it’s recyclable today, here are some additional layers of consideration for reprocessing analysis:

Potentially relevant questions for plastic packaging design Would this item be classified as Detrimental per the APR Design Guide in all or some parameters of design? Is this item considered Non-recyclable per the APR Design Guide? Is the APR Design Guide silent, ambiguous or unclear about the recyclability design of this item? If so, why? Does any industry data exist on this issue that may not be reflected in the APR Design Guide? Potentially relevant questions for plastic packaging where lab testing may be necessary Has the item been tested against every parameter of an established industry testing protocol? If an established industry testing protocol does not yet exist, or if How2Recycle has not yet officially adopted an existing protocol for that type of item, what testing protocol was followed, and why? What does the written report from the lab tests say? Does the item pass under all, some or none of the parameters? Is there additional contextual information that may help explain the results that are not in the report? If the results appear ambiguous or unclear in some way, what do you believe that suggests, and why? What is known and unknown? Potentially relevant questions for fiber packaging where lab testing may be necessary If an established industry testing protocol does not yet exist (see the How2Recycle Guide to Recyclability for more detail), or if How2Recycle has not yet officially adopted an existing protocol for that package (for example for flexible coated paper packaging), what testing protocol was followed, and why? What does the written report from the lab tests say? Does the item pass under all, some or none of the parameters? Is there additional context information that may help explain the results that are not in the report? If some of the results appear ambiguous or unclear, what do you believe they may suggest, and why? What remains unknown? For all packages Note that for polyethylene (PE) film, How2Recycle recently studied the impacts of specific innovations on the Store Drop-Off stream. Read more here. |

| End Markets | A package cannot be considered recyclable if it does not have an end market. How2Recycle has three potential end market categories for assessing the end market of a specific package. A package will be characterized as fitting one of the following three categories: — Strong end markets — Moderate strength end markets — None or negligible end markets.And then based on which end market category applies to a specific package, that package will be eligible for certain recyclability designations: — Widely Recyclable items must have strong end markets. — Check Locally items must have at least moderate strength end markets. — Items that have none or negligible end markets must be deemed Not Yet Recyclable.Each definition of end markets focuses on several key elements: — Demand. Whether the recycling industry has signaled meaningful demand for the material; and — Scale. Whether the material is getting recycled at meaningful volumes; and — Value. Whether the material carries meaningful value; and — Time. Whether value for the material has been sustained over a reasonable time period. In order to meet the standard for having an end market, a package must possess all these characteristics: demand at scale and value across a period of time. In short, positive end markets consist of: Demand + Scale + ( Value Δ Time ) Taking that basic formula into consideration, How2Recycle has developed the following 3 strengths of end market categories based on the nature of the demand, scale, and value of a material across time. Strong end markets For further definitions of some of these concepts, visit the full rule here. IMPORTANT: In addition to these end markets categories: if materials are being collected for recycling but are sent to landfill, incineration, or waste to energy to any appreciable degree, those items are not eligible for unqualified (Widely Recyclable or Store Drop-Off) recyclability claims. If this is happening to an extensive degree, an item is not eligible for any recyclability claim at all (will receive the Not Yet Recyclable label). How2Recycle may not have any data, or compelling data, for end markets on challenged packaging. In that case, it is the member’s responsibility to assemble data from some or all of the previously mentioned sources, or sources not mentioned here. How2Recycle asks members who are interested in doing this to propose a methodology that they believe would be scientifically credible to provide evidence of strong end markets for their specific item. More on that later in this Future Guide. |

This table is complementary to the Navigating the Recycling System resources by ASTRX.

Potential mitigating factors

There are additional factors about the member’s current or future intent that may be relevant, or can provide more context in the decision-making process—but do not necessarily impact the label issued. If these factors are present for challenged packages, it may soften certain concerns in other areas, but it depends on all the circumstances.

- Whether or not the member is investing in, or already executing, education efforts that may be needed to improve recyclability

- For example, if a certain package type has a high likelihood of being manually pulled out of the stream at a MRF, even if it’s desirable by reclaimers and would flow to the correct bale if not manually pulled out, what is the company doing to educate MRFs about the recyclability of this item?

- Whether or not the member is investing in, or already executing, continued end markets efforts.

- For example, if the value of a package is only known by a limited subset of potential buyers, what efforts are being taken to expand awareness of the package’s value, in a way that materially impacts the end markets for that material?

- Whether or not the member is willing to label Not Yet Recyclable on lookalike packages in its portfolio

- For example, if only one flavor of one brand the company owns is going to move to the more recyclable packaging format, and the rest of the flavors and brands with that same package format will be clearly labeled as not recyclable to the consumer, this is a positive step to help consumers know the difference between lookalike packaging.

- Whether or not the member is going to shift the design of all lookalike packages in their portfolio to the more recyclable version

- For example, if only one flavor of one brand the company owns is going to move to the more recyclable packaging format, and the rest of the flavors or brands of that member with that same package format have no intention of moving to the more recyclable format, this is less compelling than if the company promises to move all its eligible packages to the more recyclable version. Public, formal promises are better than private, informal ones.

- Whether or not the member’s peers will follow the design choices, gradually shifting the recyclability of the product category

- What is difficult in a standardized labeling system is empowering some level of innovation in packaging to push the entire industry towards more recyclable packaging, without rewarding a high level of design inconsistency within a product category that could confuse consumers longer term. If an entire product category needs to move to a recyclable structure in order for any of them to be deemed recyclable, that removes incentives for the innovative structures to gather steam in the marketplace. It is a chicken and egg problem where brands are (unfortunately) less likely to move to the more recyclable structure unless they can claim recyclability to the consumer, but if only one brand or one product is likely to move to that structure (for whatever reason), it’s potentially more confusing to the general public because it creates more inconsistency of package design in a product category.

- Whether or not the member uses recycled content in the package

- Whether or not a package is made of recycled material does not impact whether it can be recycled in the future. How2Recycle’s hope is that all recyclable packaging is someday made with recycled material, but the package being made of material that’s already been through the recycling system doesn’t impact whether we tell the public it can go through the recycling system in the future. However, it is critical that companies making recyclable packaging support the end markets for their own packaging material. Sustainable packaging is not just about what happens to packaging at the end of its life, but also what materials are selected for the package, and how it’s designed to minimize the use of materials. Accordingly, if a brand wants to ‘push’ its recyclable packaging into the marketplace without providing any sort of ‘pull’ for demand of the material, putting that responsibility on other players in the system, that is less compelling than a brand that is committed to supporting the markets for its own packaging material.

- Whether the member has made public commitments to continue to monitor and support the future success of the recyclability of the material even after it receives the desired recyclability claim.

- How2Recycle would like to avoid a situation where a member or group of members works hard on the ground to expand the recyclability of a certain package type, but stops those efforts once collection reaches a certain level. This creates risk it may be downgraded in the future if only the arguable minimum steps are taken to achieve recyclability. Recyclability is not a static thing, and history has demonstrated that relying on markets to automatically sustain viability of certain materials is a risky strategy.

Considerations for far future recyclability

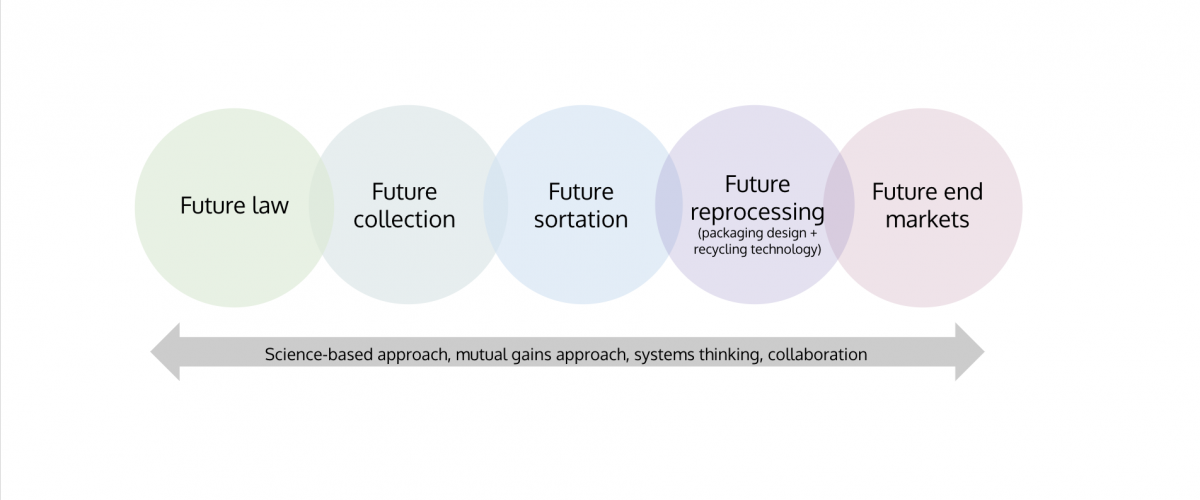

For some challenged packaging formats, recyclability at scale may be so far off into the future (5+ years) that the prior considerations are too specific. For those packages, like multimaterial flexible packaging, ‘far future recyclability’ should be considered very broadly.

| Element | Potential future assessment considerations |

| Future law | Consider (currently unknown) future FTC guidance on recyclability claims (The Green Guides are up for revision in 2022).

Might there be new law and policy in the future that may impact the recyclability of your package type or the recycling system, such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)? |

| Future collection | Depending on sortation considerations, reprocessing considerations, and end market considerations, what will the collection mechanism for the package be? In other words, how will these packages be accepted for recycling?

Will packages be collected via traditional curbside and drop-off recycling programs? Or through traditional collection with a twist (like a special bag within the curbside recycling cart)? Or through Store Drop-Off? Or through a new special take-back program? Or through a collection mechanism we don’t yet anticipate? What will be required to communicate acceptance of this item to the general public in community-facing recycling programs at scale? |

| Future sortation | Depending on the collection mechanism, and reprocessing considerations, and end market considerations, how will packages be sorted (if applicable)?

What sortation technologies will be leveraged to get the package to the right place? Current infrastructure technologies like robotics or near infrared, or technologies not yet contemplated? And/or will packaging technologies such as digital watermarks be leveraged? What will be considered ‘like’ packages for purposes of sortation? In other words, what is the scope of the packaging type for purposes of how it will get sorted, and thus recycled? Will packages be sorted with reprocessing in mind? For example, will they be sorted by different package designs? Will packages be sorted with end markets in mind? For example, will the material be sorted into different grades of value? If applicable, how can it be ensured that the sortation of this packaging type does not lead to contamination of the recycling stream for other packaging types? |

| Future reprocessing | Depending on the collection mechanism, and sortation considerations, and end market considerations, how will packages be reprocessed?

What technologies will be leveraged? Current technologies used at scale like those already at recycled paper mills, or future technologies like chemical recycling? If chemical recycling, which chemical recycling technologies may be relevant for this package type? Does the geographic location and capacity of the reprocessing facilities support the economic collection and sortation of the package? What will be considered ‘like’ packages for purposes of reprocessing? In other words, what is the scope of the packaging type for purposes of reprocessing? Will these packages be reprocessed with other materials already getting recycled, or on their own in a new stream? Will industry develop design-for-recyclability principles for this packaging type with reprocessing in mind? Has industry agreed upon a standard packaging design to ensure sufficiently similar packaging attributes to enable reprocessing of this package at scale? For example, does the package need to be more or less a single material to make recycling it economically viable, and which material is that? How will packages be reprocessed with end markets in mind? For example, will the material be sent to one or a variety of end applications? What are the requisite specifications for those end applications (dictating requisite quality of the material)? |

| Future end markets | Depending on future law, collection, sortation, and reprocessing considerations, are end markets for this material or its building blocks feasible and viable?

What is the marketable recycled material? Is it a building block for one or many materials or products or a ‘drop in’ material for manufacturing today? Are there one or many potential end markets? Do those potentially differing end markets impact how we might conceive of collection, sortation and reprocessing? What’s the economic relationship between this recycled material and its virgin counterpart? Does demand currently exist or will it exist? What drivers may impact future demand? How does potential return on investment impact the future viability of this recycled material? What is the funding mechanism for the recycling of this material (if applicable), and who will fund it? |

How the elements of far future recyclability are related to each other

As these questions above illustrate, all elements of far future recyclability are interconnected. As a result, these elements should not necessarily be considered sequentially, or separate from one another. A conclusion or insight in one element of recyclability could impact the conclusions or insights in other elements of recyclability for that package.

It’s unclear “where” this work should “start”, and whether work under each element of recyclability should occur concurrently or consecutively with the other elements. Some may argue that one element should strategically “lead” the other elements. In that case, there may not be consensus over which element should be the lead. Some may argue that work within one element should or should not overlap the work within other elements. For example, some would suggest that consensus around design for recyclability is the best starting point for specific package types, in order to scope potential end markets, and may believe that collection can be figured out later. Others may disagree, suggesting that other considerations like which relevant reprocessing technologies for that package achieve scale “first” should be the starting point. This is all to say that there is not yet industry consensus around how future recyclability strategies should be developed, and strategies may differ depending on the packaging type.

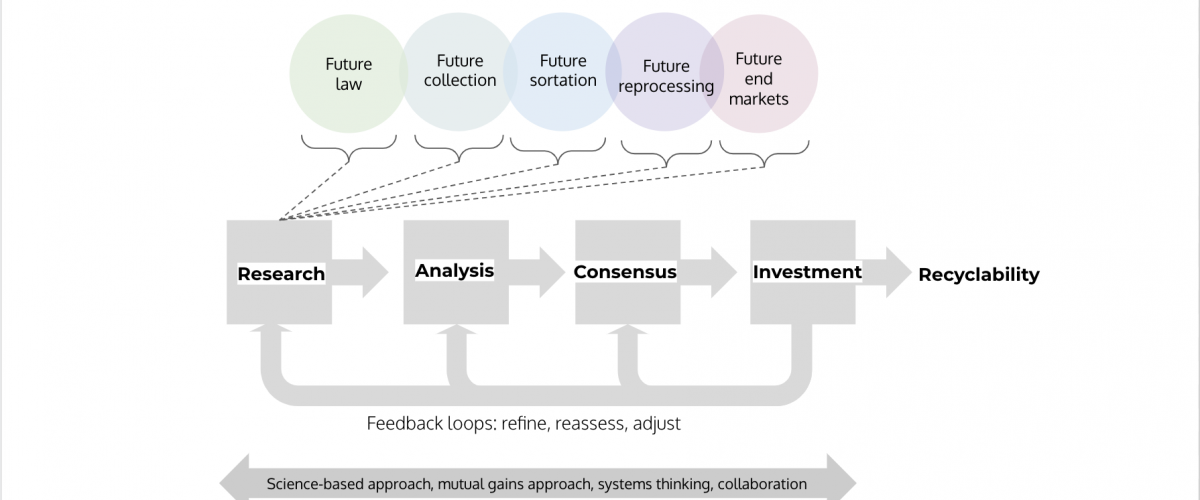

How work might proceed under each element of far future recyclability

Under each element of recyclability, there may be different levels of existing research and data for a certain packaging type. Research should be the first step of achieving far future recyclability in order to set a baseline of foundational knowledge of “where we are” in order to assess “where we want to (or can) go.” For example, what is the current state of the infrastructure and potential future infrastructure, what are the specific opportunities and challenges? Once that information has been gathered, a critical analysis should be conducted—what may still be unknown, what are variables that could impact the future, what considerations should be given priority? From that point, there should be industry consensus around what is needed to achieve scale in infrastructure investments and/or packaging design. After consensus is reached, investment in infrastructure and/or design changes is appropriate (although it may also be appropriate before consensus is achieved, depending on the specific context).

Because these considerations are interconnected and complex, efforts to develop the different elements of recyclability should be coordinated with ample feedback loops. This enables the future recyclability strategy to be refined, reassessed, and adjusted as needed over time.

Throughout this process, How2Recycle recommends these guiding principles are kept in mind:

- Science-based approach. Relying on scientific evidence and data enables informed decision-making. Relying on tradition, intuition, or other unsystematic methods may lead to solutions that are not well-designed or shorter-lasting.

- Mutual-gains approach. Understanding the interests and perspectives of all relevant entities increases the likelihood of creating value and arriving at consensus. Uncertainty can be reduced through communication and ensuring incentives and resources align with any commitments made.

- Systems thinking. Identifying and understanding patterns and connections in structures and behavior expands the choices available enables change for structures that aren’t serving purpose well and creates more effective long term solutions to systemic challenges.

- Collaboration. Broadening participation and conversation can expand collective understanding, uncover new perspectives and build trust.

Note that only after some level of scale starts to coalesce around all these elements of recyclability should a conversation on recyclability claims even begin.

Considerations for substantiation data

While we are constantly investing in new data for the benefit of all How2Recycle members, and are excited and able to take on the task of answering many of those questions for common, core packages—How2Recycle cannot research every possible recyclability question for all challenged packaging types to determine whether those packages could be recyclable in the future. For this reason, the member may need to provide its own data to ‘support the case’ for recyclability. Here are some key concepts explored in this section:

- What does it mean to ‘prove’ recyclability?

- The overall quality of data How2Recycle expects

- How much data How2Recycle expects

- How data should be presented

- How data will be interpreted

- Roles & responsibilities for data

- Commonly encountered problems in data

What does it mean to have to ‘prove’ recyclability?

First and most importantly, something can only be ‘proven’ if it exists. Assuming reasonable facts exist to support the idea that a package is recyclable, ‘proving’ it essentially means building a case for recyclability based on scientifically credible data about how that package flows through the recycling system. The member will have to gather information in an organized fashion, analyze candidly what that information means, and either make an argument for why How2Recycle should agree with that interpretation based on the recycling system today or make investments to see the infrastructure changes required in order for the package to be called recyclable.

Overall, what quality and quantity of data are required? Specifically, FTC says:

“[C]ompetent and reliable scientific evidence… consists of tests, analyses, research, or studies that have been conducted and evaluated in an objective manner by qualified persons and are generally accepted in the profession to yield accurate and reliable results. Such evidence should be sufficient in quality and quantity based on standards generally accepted in the relevant scientific fields…” Federal Trade Commission’s Green Guides § 260.2 (Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims, pursuant to Code of Federal Regulations, Title 16 Part 260). Emphasis added.

Canadian guidance on substantiation and scientifically credible evidence is extremely similar.

The overall quality of data that How2Recycle expects

Above all, How2Recycle labels must be truthful, not misleading, and supported by a reasonable basis. FTC states that to substantiate environmental marketing claims in particular (like recyclability claims under How2Recycle), a reasonable basis requires scientifically credible evidence.

For the vast majority of packaging, the way data is gathered and interpreted for How2Recycle under FTC’s guidance is straightforward. However for certain packages, there may not be an established standard outlining the exact best way to get data to answer every question that may be in the grey for recyclability. In this situation, How2Recycle is not overly prescriptive about the way data is collected but will review the data generally against the following concepts from the Green Guides, broken down into these pieces:

- Relates to who gathers the data, and for what purpose:

- Relates to how the data is gathered, and what it suggests:

- Relates to how much data is gathered, and how good the data appears:

- Sufficient in quality

- Sufficient in quantity

- …Relative to the standards generally accepted in the How2Recycle program and the recycling community.

How much data we expect

- There is no precise answer as to how much data How2Recycle needs. Some challenged packages have much more compelling cases than others and don’t require as much proof, based on context or common sense or other factors.

- When in doubt as to how much data is sufficient to prove a case, be inspired by the US legal system’s doctrine of “preponderance of the evidence” and “beyond a reasonable doubt”. As an impartial third party truthfully assessing recyclability based on the evidence presented to us, How2Recycle believes somewhere between these two standards of evidentiary proof is a sweet spot for confidently making recyclability claims. Preponderance of the evidence is the standard used in civil litigation and family law and is generally understood to mean the one party “wins” if there is greater than a 50% chance that, based on all the reasonable evidence shown, the claims are true—or in other words, “more likely true than not.” This is a lower standard than “beyond a reasonable doubt” which is used in criminal cases. The standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt” is met when the prosecutor uses facts to convince the judge or jury that there is no plausible reason to believe otherwise—that the crime didn’t occur. The standard isn’t met if after careful consideration of the facts, there’s real doubt as to whether the crime occurred. How2Recycle’s standard of evidence is informal, but falls somewhere between “more likely true than not” and “true beyond a reasonable doubt.”

How the data will be interpreted

- Package is challenged until proven it’s not. How2Recycle assumes that a challenged package is not recyclable (or Check Locally) until the member proves it’s more recyclable. How2Recycle doesn’t start this journey from the point of the member assuming a package is recyclable and it’s How2Recycle’s job to prove that wrong. Rather, How2Recycle assumes the challenged package isn’t recyclable, and the member presents a compelling case that it is.

Roles and responsibilities

- Burden of proof is on the member. This means that the member is responsible for acquiring and sharing the data to support that the package is recyclable if How2Recycle does not already have that data in-house.

- Burden of persuasion is on the member. This means that member is responsible for ‘making the case’ with that data and persuading that the package is recyclable. Why should How2Recycle look at the data a certain way? What does this data mean?

- No one else is qualified to tell you what How2Recycle label applies other than How2Recycle. No other organization is authorized to dictate what type of data is sufficient and compelling to get a label. Consultants and other organizations can help usher you along in this process and their opinion can be something How2Recycle potentially takes into account, but does not dictate the outcome.

How the data should be presented to How2Recycle

- Explain yourself. When findings are presented to How2Recycle, the key word is because. All too often How2Recycle receives conclusions from the member based on the data, but there is no reasoning that connects the data to the conclusion. Why do you think what you think? Because, because, because.

- Organize arguments into clear segmented supporting points. It’s more persuasive to say that a certain conclusion is true if it’s explained it’s for X number of reasons, and then those reasons are discussed one by one.

- Alternative arguments are acceptable. This means presenting more than one potential outcome for a package even if those different outcomes contradict each other. For example, “we believe that our packaging should qualify for the Check Locally label, but we also believe that our packaging should qualify for the Widely Recyclable label.” Providing an argument for each means that multiple options are available if the ideal or desired outcome isn’t possible. It’s OK to throw multiple things up on a wall and see what sticks. How2Recycle doesn’t judge a member for possibly appearing self-contradictory. This is an everyday occurrence in the field of law that helps tease out potential benefits and risks of different outcomes.

- Avoid incomplete sentences or bulleted lists without accompanying written explanation. Power Points are helpful if they are a cherry on top of all the other data you’ve sent us. The devil is in the details and How2Recycle wants the whole body of evidence, not just the highest level summaries.

- Approach this journey by attempting to make a compelling argument with solid supporting evidence. Recyclability assessments aren’t a negotiation—for members’ benefit and How2Recycle’s, How2Recycle is legally required to take things carefully step by step, and all members are held to the same standard of scientifically credible information. How2Recycle is unable to make special exceptions or deviate from the established process.

Commonly encountered data problems

- Redacted data or summaries only. While Power Points and freestyle conference calls may be the modus operandi of the business world, in order to substantiate a claim legally, How2Recycle needs full documentation. Summaries are important and helpful to include, but only sharing summaries is insufficient because they can be inaccurate or incomplete. How2Recycle will feel confidence when the entire body of evidence can be assessed as a whole.

- Nonrepresentative data. This means the data provided is not representative of the ‘average’ or the big picture of the concept being measured. For example, if a member wanted to show how a package flowed through a MRF but picked the most technologically advanced MRF in the country that is ahead of all its competitors in terms of sorting equipment, that is not representative data. It doesn’t mean it’s irrelevant, but it’s less compelling than a flow study at a MRF that is more or less average in terms of capabilities, throughput, etc. Sometimes the question of what is actually ‘representative’ is difficult and not straightforward. How2Recycle does not have answers for what representative means in all contexts. In these cases, How2Recycle urges members to ask themselves, what do YOU think is representative? What does the member’s legal team feel comfortable with? Start there, and we can respond to any proposals before the member invests in data acquisition that may not be representative of that thing the member is trying to measure.

- Lack of explanation of methodology (and reasoning behind why it was chosen). Sending How2Recycle a document with numbers and conclusions without context or detail as to how the member arrived at those conclusions only generates more questions than How2Recycle had to begin with. And why did the member choose to measure it in this way—what is the member’s reasoning for taking this strategy? Providing this information goes a long way to putting the data in context and helping How2Recycle build confidence in the methodology chosen. How2Recycle also needs to see the calculations behind quantitative conclusions.

- Missing data. For example, if a member said it tested under parts 1 and 2 of WMU’s SBS-E protocol, but part 2 is missing from what was sent to How2Recycle, How2Recycle will have to ask member to provide that. Do not omit data.

- Contradictory data (unless you acknowledge and interpret the contradiction). There are two types: data that contradicts itself (within the same study or data set) or data that contradicts other data (that How2Recycle may have on file or that member knows may exist otherwise). In this instance, How2Recycle expects the member to acknowledge and explain the contradiction—this not only builds credibility and trust, but also expedites the process. If that explanation is not persuasive, How2Recycle will likely require more data to overcome the discomfort from the contradiction. But data can also contradict itself. This means it either doesn’t make sense or can’t be explained, or is ambiguous in a way such that two opposing conclusions may be possible. This is more common than not, because the recycling system is complex and straightforward answers do not always exist. The presence of a contradiction is not a dealbreaker for your item—in fact How2Recycle expects at least a small amount of ambiguity or differing opinions in anything by the nature of recycling.

- Data that doesn’t answer the question that was asked. This could also be called nonresponsive data, or irrelevant data. For example, if How2Recycle asked whether hand pickers at a MRF are likely to pull this item off the conveyor because they are trained to consider it a contaminant, but in response member presents optical near infrared equipment sortation data showing it sorts correctly 75% of the time, that does not answer the question of whether humans will pick it out anyway (either before or after the optical sorter does its job).

- Only highlighting favorable data, or omitting or glazing over less favorable data. Build credibility through full disclosure. Put the data in context to suggest why it might be this way.

- Data that isn’t objective. For example, polling a company’s own employees about their personal opinion on a matter is not objective data.

- Not considering differences between qualitative and quantitative data and what might be more compelling in certain instances. Quantitative data is numbers—it relates to quantities or specific measures of things. For example, a specific additive in PET may increase yellowing for recyclers at X% when used at Y% concentration. Qualitative data is descriptive and not measurable in the same way. For example, a trade association representing PET reclaimers publishes that they consider a certain type of closure detrimental to their recycling process. Both types of data are relevant and important in interpreting recyclability; qualitative data can tell us about behavior and dynamic realities or illuminate realities that are very difficult to measure; quantitative data allows us to make statistical comparisons and inferences in a more predictable and fixed way. Both types of data may illuminate the other. This is just something to think about in the journey. Think like a scientist.

Recommendations for strategizing future recyclability

What members should keep in mind if they go down this road.

At How2Recycle, we say design your packaging to fit the existing recycling system, or change your packaging. It’s as simple as that. But, some companies don’t like that answer. Some want to keep their existing packaging but ask the system to change. That is a harder road. That is what some of this guidance is for. But understand that’s swimming upstream.

How2Recycle recommends a longer-term, holistic approach to packaging sustainability. Just because a company has challenged packaging doesn’t mean the company should try to achieve a recyclability claim in the short term (short term generally means immediately to 3 years from now—but it depends on package type). Many companies understand that their packaging is challenged within the existing recycling system and instead of pushing for ‘recyclable’ today, they are focusing their energies on other strategies. For example, by investing in chemical recycling infrastructure or doubling down on other important sustainability attributes of their packaging like maximizing use of recycled content (PCR) and selecting safer packaging materials.

How2Recycle observes that companies are most aggressive about challenged packaging when all or a substantial portion of their business relies on it, and the company wants to maintain the status quo of its business to the maximum extent practicable while not losing customers because of the weaker end-of-life story. Some believe the recycling system will or should adapt somewhat to their packaging and economic interests. More diversified businesses, or those taking a holistic, longer-term perspective on sustainable packaging are less likely to press to get their challenged packaging to be deemed recyclable, and understand that the economics need to benefit all parties.

That said, we are environmentalists, and of course would like to see more valuable items deemed recyclable, leading to more materials getting recycled. How2Recycle loves and embraces innovation (both in packaging and the recycling system), because without it, we cannot evolve and build resilience. For this reason, for certain packaging (those that face an easier road to recyclability than others), pursuit of recyclability claims can be a meaningful and worthy one if that effort is executed thoughtfully. But if a company decides to go down this road, expectations should be managed, and investments should be expected.

| You may be thinking, “but don’t the recyclers want my packaging today?” Understand that recyclers probably don’t need a challenged package, or at least they don’t feel that way today—otherwise it’d already have a Widely Recyclable label. The package “not being worth it” to recyclers may be due to a combination of factors such as its very low volume in the stream, an undesirable yield loss, or a lack of data to convince recyclers of otherwise. One specific package may constitute a very, very small amount of a recycler’s potential feedstock, and so the recycler may not perceive it as a priority worth dedicating time or effort towards. For example, a recycled paper mill might use 10% mixed paper (classic paper packaging like cereal boxes) and 90% corrugated boxes, so a company arguing that a special paper soap wrapper (with a new type of coating there is no reprocessing data about) should be considered recyclable because it is X tons of fiber per year is not always persuasive. That’s because at best it’s a fraction of a fraction of a single percent of what a recycler receives and so not as significant as it may seem to the company that produces the package. The notion of ‘yield’ in recycling is very important—packages that aren’t designed for recyclability increase yield loss for recyclers, negatively impacting their bottom line. Yield loss comes from things that simply don’t belong in the recycling stream, like food waste or nonrecyclable materials, but also comes from packaging attributes like coatings, attachments, or fillers that do not provide any value, or even at times may proactively reduce the value of the recycled material. Recyclers pay to have the contamination come into the facility (so they can remove it from the saleable recycled material via reprocessing) and then pay again to have it landfilled. Recycled paper mills can spend millions to install a single piece of equipment to increase their yield or decrease their contamination by a mere 1%. The more feedstock that a recycler receives that does not give them a decent return on the investment of buying that material is better worth leaving out of the stream. Some companies believe that even though their packaging design may create some positive yield for the recyclers but that same package is also known to create a certain level of contamination, it should still be considered recyclable because the rest of the stream would “dilute” it. While some level of contamination is an unavoidable reality that recyclers already deal with, How2Recycle does not find dilution arguments compelling. Many packaging formats have the potential to substantially increase in volume over time (sometimes in difficult-to-predict ways), especially if you observe changes over the last decade in what we refer to as ‘the evolving ton.’ So, even if it might be diluted now, that can’t be guaranteed into the future; what adverse impacts might that cause the recycling stream? Approaching the recycling system as if a company has a gift for it (“size of the prize!”) is sometimes inaccurate (but not always) and could have the inadvertent effect of conveying to the recycling community that the company lacks an understanding of the economics of recycling. In order for something to be recyclable, someone needs to want to buy it… and so far no one has been biting. Or maybe they would bite, but there is a lack of persuasive data to make that case. |

Whose job is this to figure it all out anyway?

Companies should be prepared to roll up their sleeves if they have a challenged package they want to be considered more recyclable. While How2Recycle works hard to continually expand and improve its understanding of recyclability, spending significant amounts of resources on building the case for certain challenged packages is outside the scope of our work. How2Recycle invests in data to understand the recyclability of certain packaging formats better, but the program has a select amount of these projects each year and How2Recycle does not prioritize challenged materials as a general matter. This means that while How2Recycle might study and acquire data on a challenged package someday, it is not appropriate for us to do so at this time. Note that if other organizations or consultants want to lead or do this work on a member’s behalf, they are not the authority of the standard or decision-making process for How2Recycle. How2Recycle appreciates being made aware of work being done and is happy to provide members feedback on a proposed plan for future recyclability but will not lead this work for members’ behalf and How2Recycle will never delegate its decision-making to another organization.

Managing expectations

The journey to future recyclability can be long and complicated. From How2Recycle’s experience, one should be prepared to:

- Expect long timelines. Although some companies are focused on how far away from commercialization they are, or how far out their artwork deadline is, these considerations cannot play a role in the determination of recyclability at How2Recycle. How2Recycle understands that brands are used to moving quickly in the consumer packaged goods (CPG) space, but it takes time to change the recycling system, or to collect and interpret meaningful data. Even if a member has built a compelling case for something to be called recyclable, it still takes time for that case to be interpreted and discussed within the recycling community and/or the How2Recycle program, depending on the circumstances. If a company has challenged packaging, consider the journey to recyclability to be more likely years, not months or weeks.

- Anticipate moving targets. As much as How2Recycle would like to say “this is the exact checklist” and not adjust it so that businesses can have that certainty, How2Recycle just legally isn’t able to provide that guarantee. How2Recycle does not want members relying on a snapshot of the recycling system in time when in reality it is highly dynamic and changing. Moreover, How2Recycle is constantly learning and improving its understanding of recyclability and thus becomes more sophisticated over time and may grow to expect more from members as our industry evolves. That said, How2Recycle knows that companies are investing significant time and resources into new packaging designs and infrastructure investments, and thus want to provide some idea of the journey.

- Be prepared to invest. Companies may need to invest in (a) data, (b) infrastructure, or (c) both. This can be anywhere from a few hundred dollars for a simple screening lab test to millions of dollars to fund on-the-ground end market development in multiple geographic regions. There is no one-size-fits-all.

- Companies will hear conflicting points of view about their package. Once members start investigating a package’s recyclability, without question there will be opposing opinions on it. If there was consensus about this package, it wouldn’t be considered challenged packaging. Recyclers don’t complain about steel soup cans—those are core items and are not under dispute. If a member comes to How2Recycle and says a MRF in a city told the member the package is recyclable, that’s great, but not surprising. The issue is proving it’s recyclable at scale across the country, in a majority of the instances. This is the task ahead.

- You may not get the result you desire. There is risk that members will go down the road and uncover unflattering truths or difficult roadblocks, or the recycling system may change. This is an unavoidable risk in the journey to recyclability.

Tips to expedite the journey to recyclable

- Consider banding together with your peers to build a stronger movement together. This can manifest in two ways: first, consider working directly with competitors, so companies aren’t doing duplicative work. How2Recycle has observed first hand how competition-obsession and secretive postures prevent progress because if the two competitors had been talking to each other, certain pitfalls or expenditures could have been avoided. Second, consider joining forces with companies using similar, but different, packaging formats. How2Recycle sees converters and brands of hot paper cups fight to get their cups called recyclable, but cold paper cups face a similar plight, as do fiber ice cream containers. They are all very similar—paper packages with different coatings and similar food contamination concerns. Wouldn’t it be easier if those three groups worked collaboratively? Sometimes there are political concerns—”oh, we don’t want them in this, they are food service, we are grocery”—but if a company goes solo because of this, How2Recycle cautions that waste could be created or potential limited.

- Challenged packaging needs leaders. Within these loose collectives, or groups with a shared interest, it’s possible that nothing may get done if one or two companies or organizations don’t rise to be the leader(s). Consider leadership. See the later section about models.

- Be strategic about who takes on this work inside your organization. Who works on this journey within a company can make a difference. While it’s by no means a requirement, because of their analytical skill set, attention to detail and “no until yes” temperament, How2Recycle recommends legal teams get involved with this project—it’ll possibly save some headaches. How2Recycle has observed that others in the company who work closely with specific packages may be so tied up in a specific outcome that they may lack the objectivity required to endure the journey to recyclability and may overlook critical obstacles or considerations. However, they may be the best individuals to navigate complex technical considerations like reprocessability and dense lab results.

- You probably can’t buy your way out of this—unless you go really, really big. It all depends on the situation, but in many cases, throwing a few thousand dollars at the issue (like to get a lab test completed) may be insufficient. Millions or billions of dollars (in some but not all cases) could potentially be required to impact a package’s recyclability at scale in the US and/or Canada. In most cases, actual work needs to be done like installing new recycling equipment at scale, influencing attitudes or recycler behavior, building end markets city by city, or creating an entirely new bale specification (but these aren’t the only ways). Investment at scale is almost always required if companies want change.

Member expectations: commonly encountered challenges

- Member is only focused on positive aspects of the recyclability story. Sometimes a member may only acknowledge the optimistic possibilities of a package getting recycled, and disregard or downplay how the package is challenged. This slows down the process because How2Recycle has to tease those challenges out over a longer period of time and play the role of rebutting or explaining to the member why their assessments are overly optimistic. In other words, confronting the realities of a package’s challenges will expedite potential success.

- Misunderstanding the mission of How2Recycle. While How2Recycle understands that there are commercial interests in play in getting a positive recyclable claim for a package, How2Recycle’s interest is only the truth of whether something is recyclable. No individual member funds a substantial portion of the program, and How2Recycle’s low, flat annual fee structure and diverse membership base enables the program to remain independent. Ultimately, we are communicators, and How2Recycle’s goal is to provide the general public with accurate recyclability labeling. Note that members do not, have never, and will never choose their own How2Recycle label.

- Member is not open to outcomes or strategies not previously considered. A member may be so dead set on getting a specific outcome or following a specific strategy that other opportunities or alternative plans for future recyclability along the way could be missed. Flexibility can help companies adapt to shifting realities and sometimes certain desired outcomes are not possible at this time.

- Not all at your company on the same page. In some cases there is a lack of information sharing that causes confusion and duplicative actions within a company, and that has an impact on the success of your efforts. But How2Recycle has also witnessed profound disconnects on the recyclability of a package from different people in the same company. If a packaging converter company also owns paper mills, How2Recycle cannot only listen to the converter side of the business and disregard the concerns of the recycling side of the business. If one ice cream brand within a company isn’t talking to the other ice cream brands in the company, efforts can be duplicative and confusing. How2Recycle encourages everyone to get on the same page for the best possible outcomes.

Previous models for achieving recyclability

There are a variety of successful approaches How2Recycle has observed that result in making packaging more recyclable. A forthcoming report from ASTRX will explore this in greater detail to provide companies with inspiration from recent successful models.

Steps for members to achieve future recyclability

The first step towards recyclability should be submitting a label request to the How2Recycle team to confirm the label that it would receive today. This sets a foundation for where the package is today, so members can compare that to where they’d like to be. Along with the How2Recycle label, the program will provide specific recommendations for design improvements to make the packaging more recyclable. This is the starting point to understand generally what the issues are, but because challenged packaging is complicated and nuanced, the label does not always tell the whole story. This first step is critical so companies do not make incorrect assumptions about their packaging.

The second step is sharing your intent on your package’s future recyclability with How2Recycle. This is OPTIONAL—if a company has a challenged package, the member doesn’t need to let How2Recycle know, and if the member is not going to pursue future recyclability, How2Recycle doesn’t need to know that either. But if the member intends to try to create future recyclability, it’s advised to give How2Recycle a heads-up to help avoid any unforeseen road bumps in the details. For example, maybe How2Recycle just learned something that would impact the guidance the program gives a member on a package (note that significant learnings are proactively shared with all How2Recycle members). Accordingly, please send a note to how2recycle@greenblue.org. How2Recycle recommends your email communication follow one of these formats

- We have a challenged package (include label request URL from How2Recycle Member Platform) and we are going to take on the task of building a case for recyclability. OR

- We have a challenged package (include label request URL from How2Recycle Member Platform) and we would like to explore whether we should take on the task of building a case for recyclability.

- Helpful details to include:

- Who the member has designated as the internal primary contact on this matter (How2Recycle has had companies unintentionally duplicate effects because multiple persons in a company reach out regarding the same thing, or certain important people may not be looped in, creating information gaps)

- Whether or not you’d like How2Recycle to share your company’s name with other companies with the same challenged package—possibly we could give you each other’s contact information for potential collaboration? Are you an SPC member? The topic may be eligible for one of our Collaboratives.

- Whether you intend to work with a specific organization or consultancy to help you navigate this process (not required).

- What your general expectations or hopes are (time-wise, and what exact result are you hoping for?). This gives How2Recycle some additional context in case we can give you any important initial feedback.

We will confirm the receipt of your email and give any feedback we are able to at that time. Based on the novelty and complexity of the issue at hand, an additional conversation may or may not be appropriate. Of course you can change your course of direction from the above avenues at any time—just let us know.

The third step is coming up with a plan for achieving future recyclability based on the guidance in this Future Guide, and sharing that plan with How2Recycle. Do not take action on your plan yet—we don’t want you to think you need to do a certain thing, when in fact that may not be the appropriate thing. How2Recycle is happy to vet a member’s plans to save time and money before a member starts off on a journey.

How2Recycle will need to see plans in writing. Telling staff verbally what your plans are is insufficient because the program needs a paper trail for clarity, and due to the complexity in this space, How2Recycle needs time and opportunity to fully prepare our feedback.

What that plan to achieve future recyclability looks like depends on the member. The intent of this Future Guide is to provide as much constructive, specific guidance as possible to demystify the process and How2Recycle’s impartial perspective on it. That said, How2Recycle is not so bureaucratic as to prescribe a specific approach for every single challenged package of the future. That’s because most of the time, we may not know the answer, or a specific approach could be arbitrary. There are always grey areas and unknowns when a member is trying to push the frontier forward.

This is the point in the process where How2Recycle flip the burdens on the member, for you to ask yourselves what you think is a good journey to future recyclability (given our guidance outlined here). As much as How2Recycle would like to say we know all the answers, we don’t. We are open minded about how you build your case. We just need the case to be a good one.

The fourth step is to follow your plan. And to keep How2Recycle updated! Keeping How2Recycle updated helps ensure you are still on a confident plan for future recyclability. At this point How2Recycle only needs to know high level information; the program doesn’t need to be involved in the details of the process.