What is Store Drop-Off?

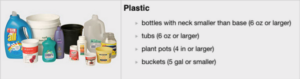

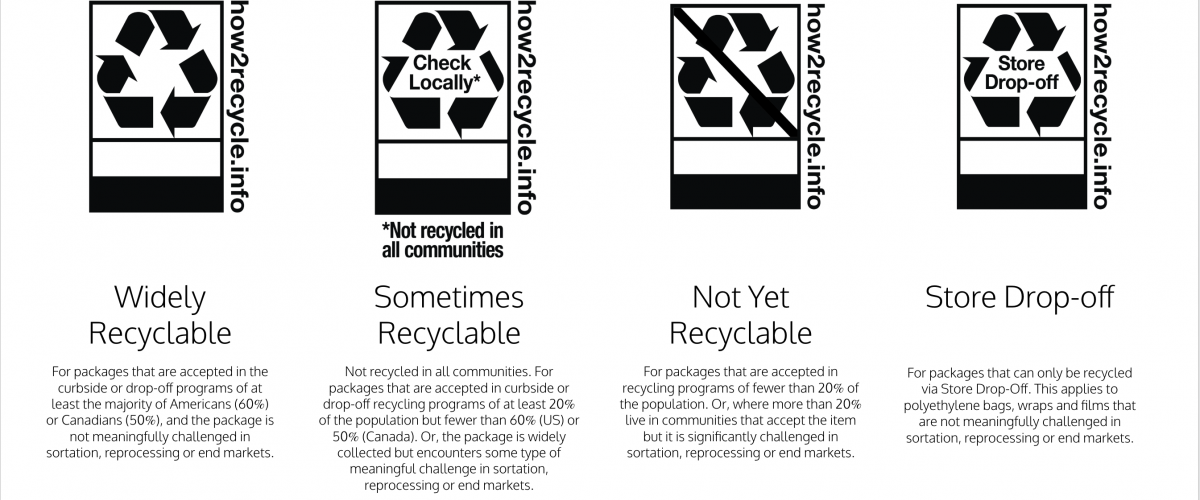

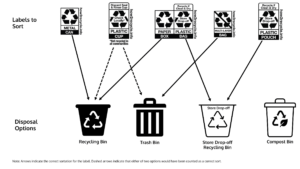

The Store Drop-Off label applies to certain flexible polyethylene (PE) film packaging, such as bags, wraps and pouches. Through Store Drop-Off recycling, consumers can take items featuring this label—like the wrap around paper towels, produce bags or certain stand up pouches—to their local participating retail location to recycle along with any plastic shopping bags.

Store Drop-Off collection bin at a Target.

The Store Drop-Off program is available to the majority of the population in the United States. It is not owned or operated by any central or unified entity. Rather, individual retailers set up their own collection systems, sometimes in collaboration with specific PE film recyclers or programs like American Chemistry Council’s WRAP.

The material collected through Store Drop-Off is recycled into a variety of end applications, the most dominant being composite lumber and plastic shopping bags. According to the most recent data available, over 225 million lbs of material were recycled through Store Drop-Off in 2017.

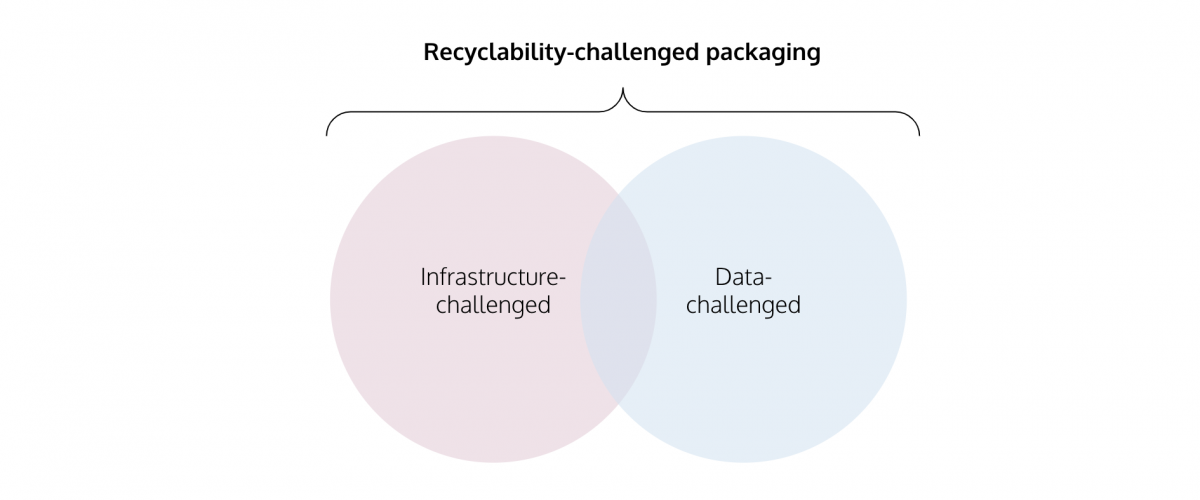

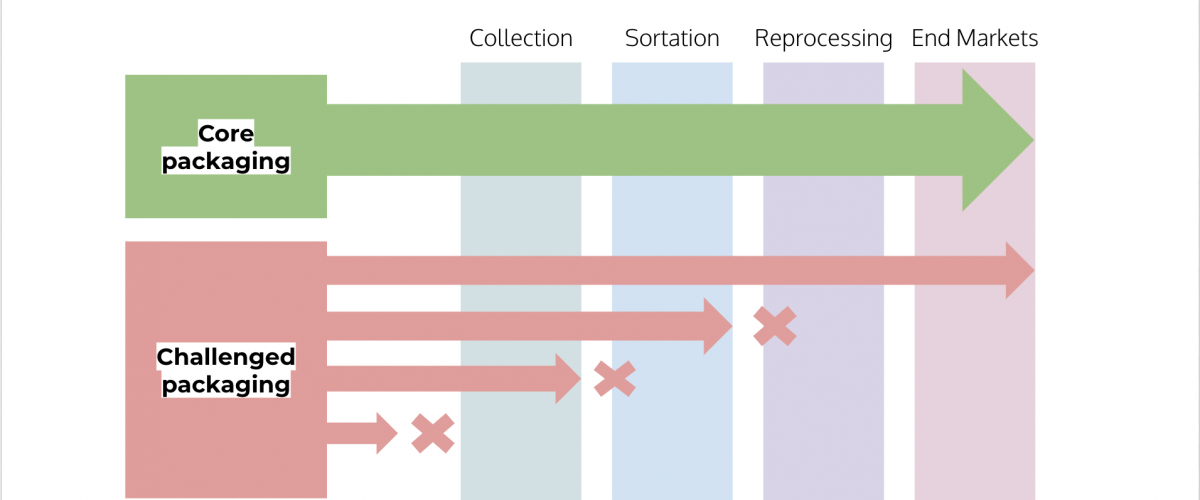

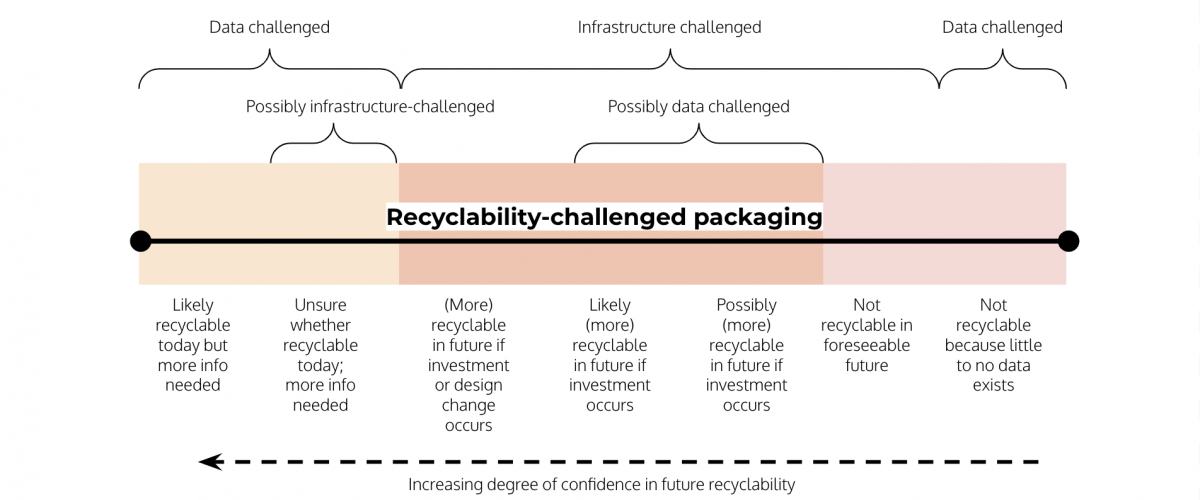

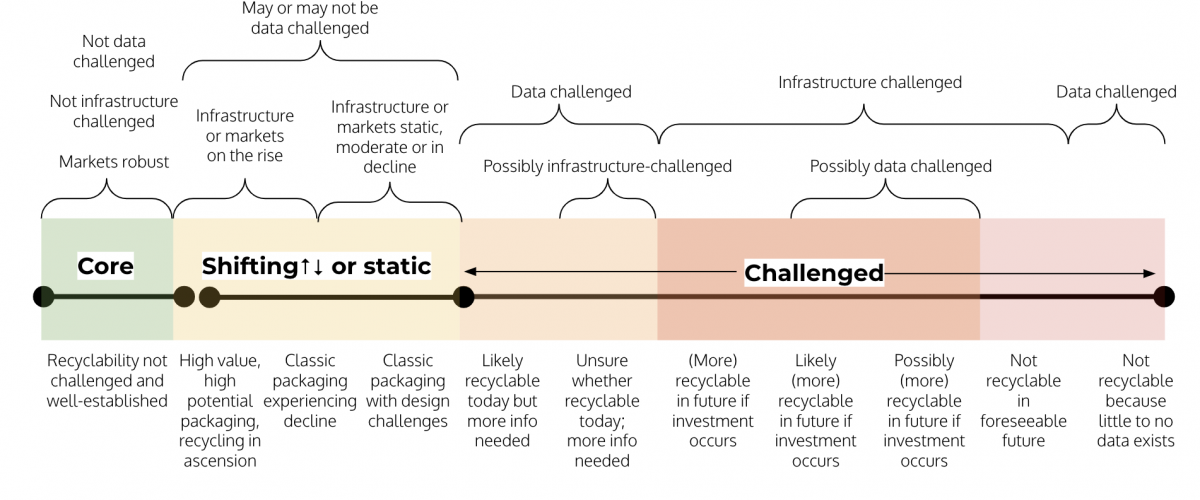

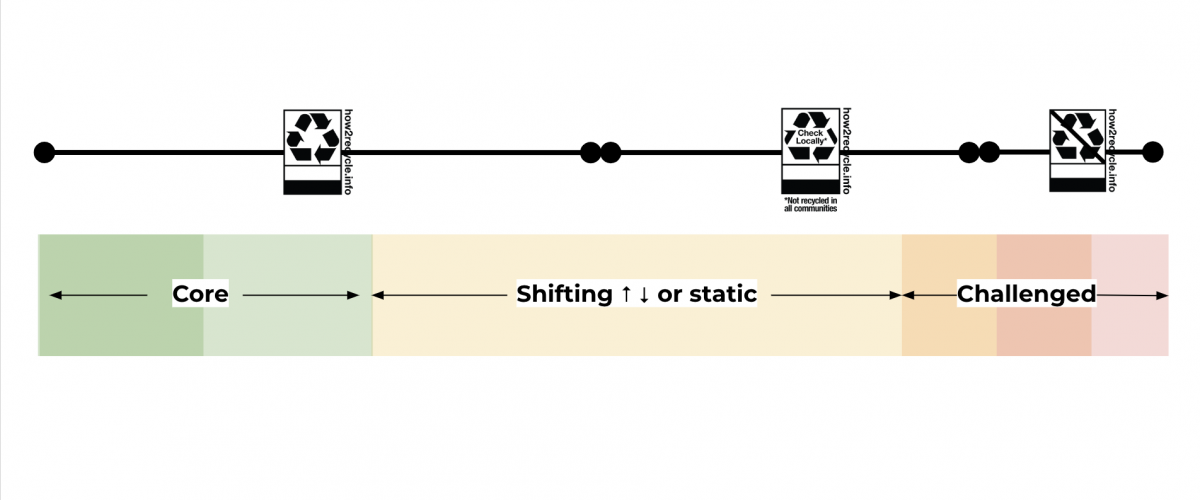

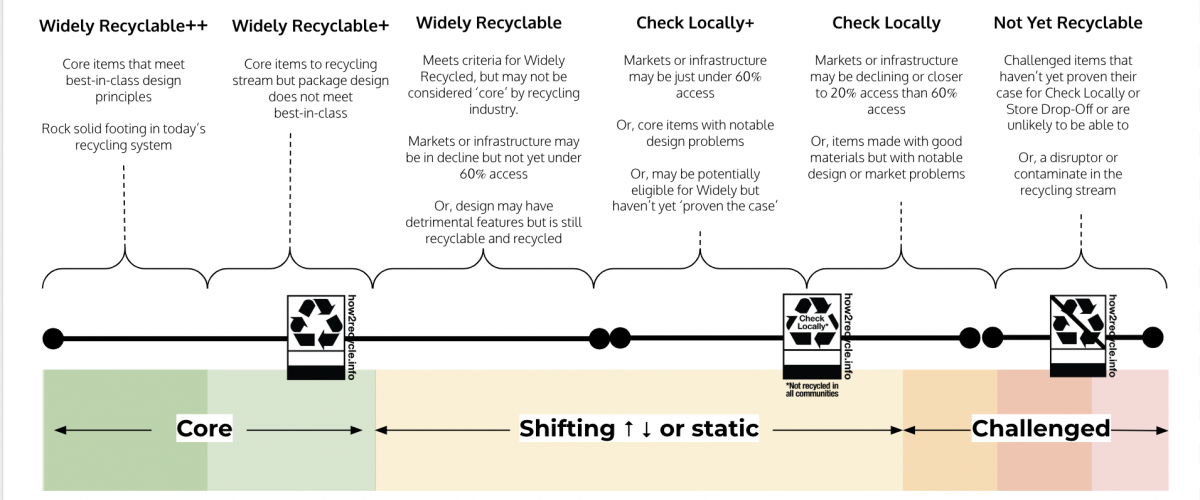

The recyclability challenge for flexible packaging

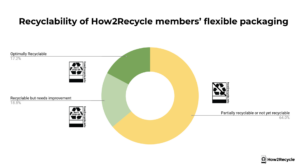

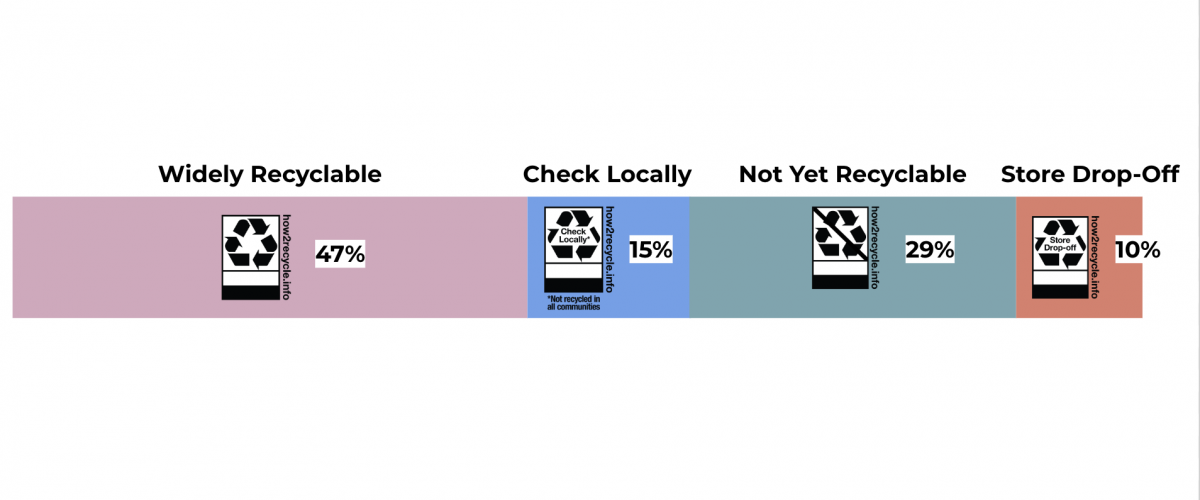

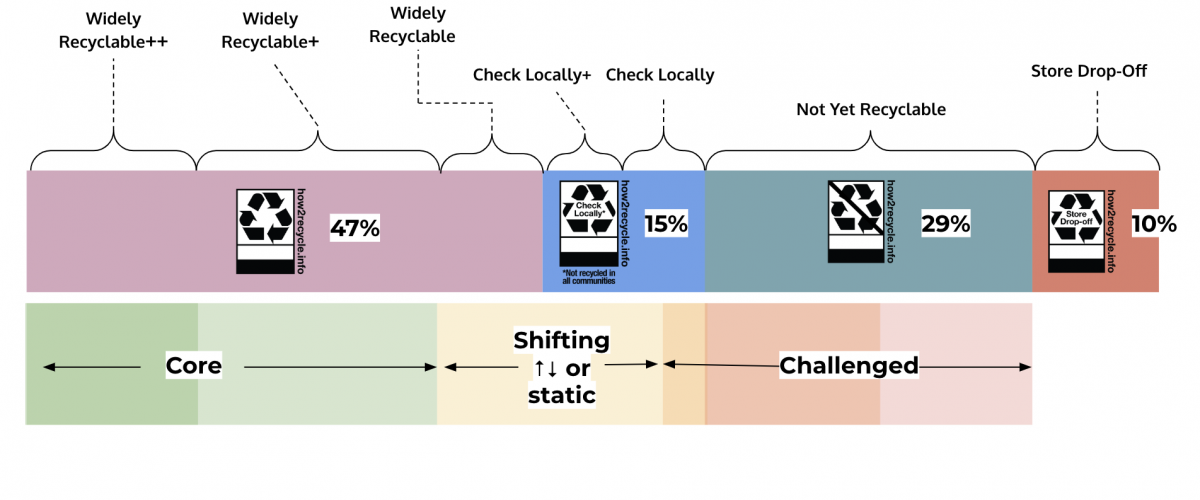

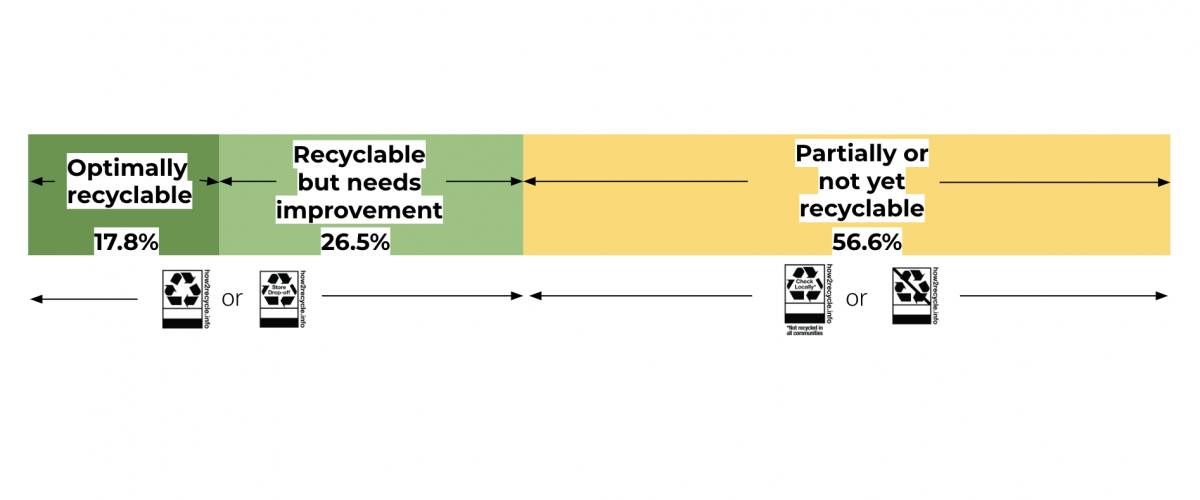

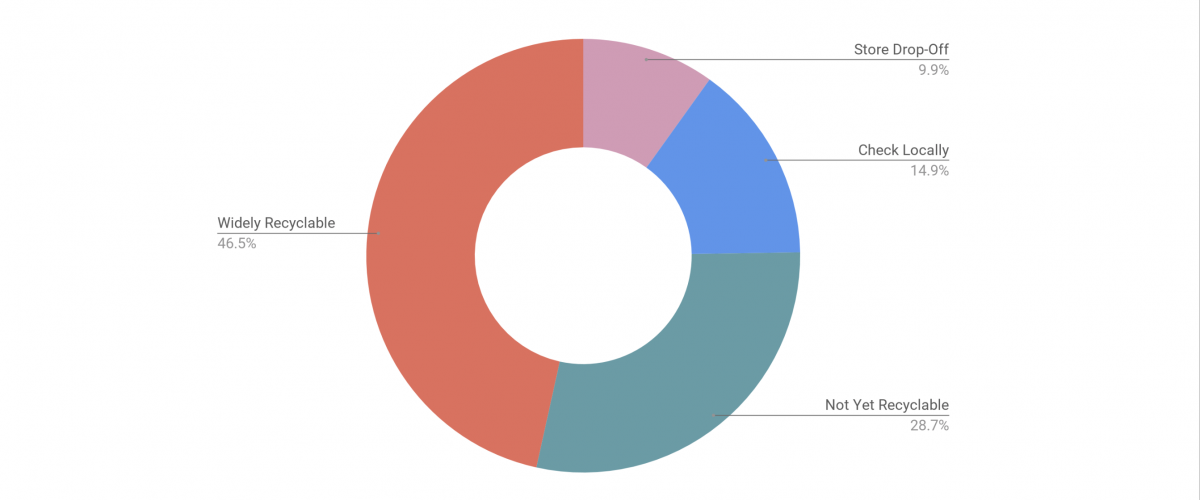

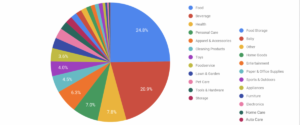

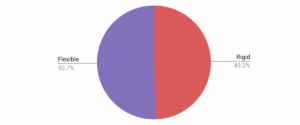

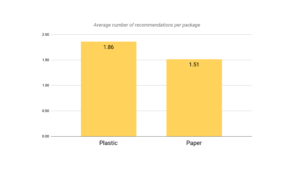

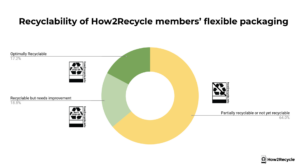

About half of How2Recycle member packaging components are flexible, such as bags, wraps, pouches, and wrappers.

Store Drop-Off is the only recycling option for flexible packaging at scale, and is only available to polyethylene flexible packaging.

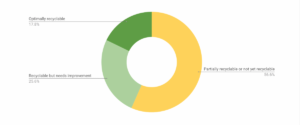

While about 36% of members’ flexible packaging receives the Store Drop-Off label, the remaining 64% is Not Yet Recyclable:

Accordingly, flexible packaging is far and away the biggest and most challenging recyclability challenge facing brands. The marketplace is experiencing an unprecedented explosion in flexible packaging, most of which is not recyclable. This is almost half the entire challenge for companies to hit recyclability goals (see the Recyclability Insights report for more detail). While some product categories can be very easily changed to Store Drop-Off packaging today, others, such as those containing wet and sticky products or those requiring a very high performance barrier, require recycling system interventions. These interventions may include new or different collection mechanisms for reprocessing technologies like chemical recycling. See the “Considerations for far future recyclability” section of the How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability for more detail.

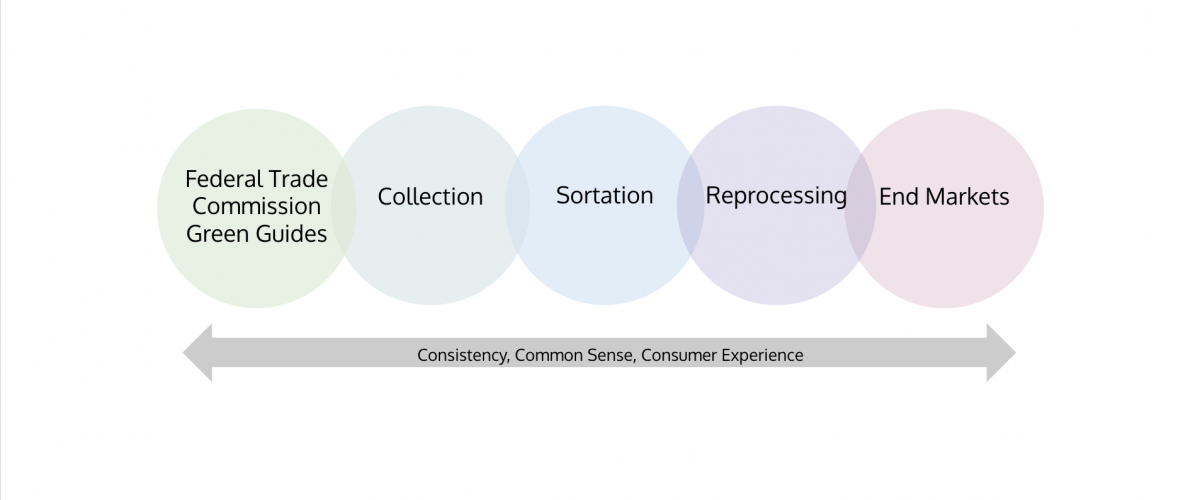

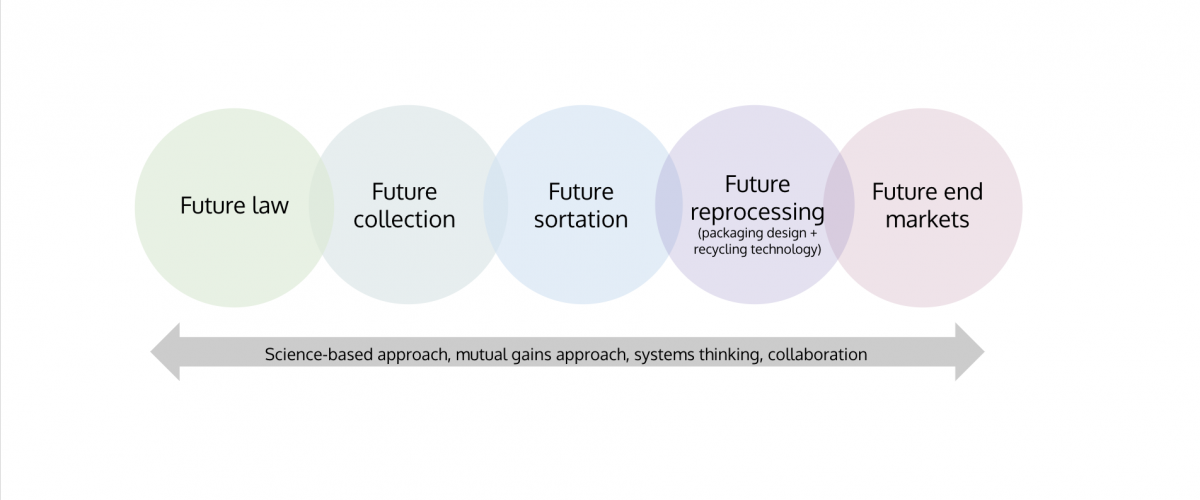

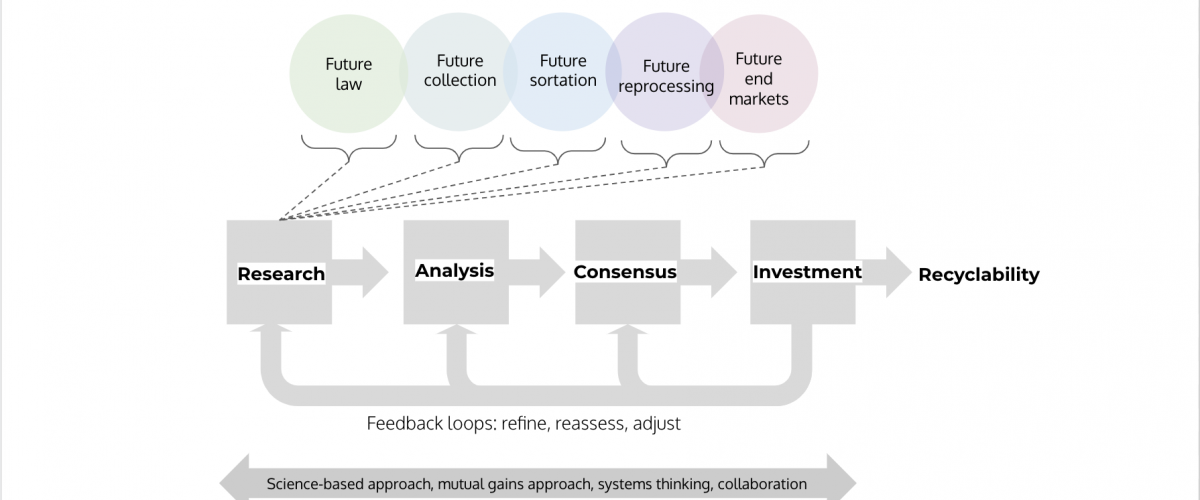

However, the ability of the Store Drop-off stream to alleviate the packaging industry’s end-of-life challenges with flexible packaging is limited long term. Like all recycling streams, market volatility in the global commodities context is a challenge. But for Store Drop-off in particular, the demand for the material, its current recycling rates, and the challenges inherent in Store Drop-off collection (consumer convenience, reliance on retailer participation), along with the enormous volumes of flexible packaging that are being produced, suggest that its long term potential for all or most flexible packaging is insufficient to meet recovery needs. Accordingly, How2Recycle recommends that brands, packaging producers and resin manufacturers critically analyze what wide-reaching collection, sortation, reprocessing and market mechanisms and investments are required to scale recyclability of flexible packaging for the far future. See the How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability for more insight.

Still, many packages that are Not Yet Recyclable today could be moved to Store Drop-Off recyclable material, and much of that is low hanging fruit from an implementation perspective.

PE film provides excellent moisture barrier, is transparent, and carries a lower carbon footprint than most rigid packaging. For this reason, it is potentially suitable for many packaging applications. Too many companies are still using nonrecyclable plastic films (made of materials like polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or a combination of resins) to package products, when Store Drop-Off recyclable PE could be used instead. The most frequent example of this is products that require no moisture barrier but are packaged in PP film—the high clarity, crinkly bags. For example, you may see PP bags for certain apparel bought via e-commerce, or bags holding individually wrapped candy. Chances are, the package design could be changed to PE so that it can be recycled via Store Drop-Off.

For other product applications that may require a certain oxygen barrier or greater strength than traditional PE film, innovation is happening at a rapid pace in the packaging industry. For example, technology in PE film packaging has enabled products like granola that previously would not have been sufficiently protected by PE pouches to become Store Drop-Off recyclable. In order to ensure that these increasingly sophisticated and fast-proliferating innovations can be labeled as Store Drop-Off recyclable, especially as flexible packaging is the fast growing segment in packaging, How2Recycle needed to learn more—and so began this study.

This How2Recycle Store Drop-Off Film Study illuminates design considerations for flexible polyethylene packaging in the present and into the future for How2Recycle member companies seeking to make more recyclable packaging.

What is the How2Recycle Store Drop-Off Recyclability Film Study?

How2Recycle launched an in-depth Store Drop-Off film study in 2018 in order to:

- Better understand the Store Drop-Off stream.

- Better understand how certain PE film innovations may impact the Store Drop-Off stream.

- Identify the most appropriate test standard for Store Drop-Off recyclability.

- Be in an informed position to provide R&D; guidance to members for PE film.

Multiple phases of this study included on-site PE film recycler visits and extensive testing of current Store Drop-Off material and specific PE film innovations together with How2Recycle’s third party lab partner for this project, Plastics Forming Enterprises. Over 4100 pieces of quantitative data were generated and closely analyzed.

Design of the study

The study design focused on two key areas: first, understanding the Store Drop-Off stream, and second, understanding the potential Store Drop-Off recyclability of certain PE film innovations. For the first part of the study, to understand the current recycling stream, How2Recycle sought to answer these questions: What material is in the stream, exactly? How does that material behave as a whole? How do specific materials in the stream behave?

And for the latter question, How2Recycle asked, how do different PE film innovations behave from a material perspective? How do those materials compare to the Store Drop-Off stream? How do those materials compare to one another?

As a result of these two focus areas, How2Recycle’s goal was to identify the best way to assess PE film innovations against the stream in order to set a standard for Store Drop-Off recyclability.

Phases of the study

The need for a clearer standard and test protocol for assessing Store Drop-Off recyclability was first identified in 2017. The study began in early 2018 and ran through 2020. The current Store Drop-Off stream and specific PE film innovations were studied concurrently, and complemented by on-site visits with three PE film recyclers. Throughout this process, the scope of work was expanded to accommodate additional innovations of interest, as well as acquire greater levels of detail in lab testing than what was initially envisioned. The data gathered was continuously analyzed so that the trajectory of the study could be adjusted to new learnings.

Plastics Forming Enterprises (PFE) is an independent third party lab with significant testing expertise in plastics recyclability globally. How2Recycle worked with PFE as a partner on this project, relying on their technical knowledge and skills to not only shape the study design, but also analyze the data coming out of it with their decades of experience and science-based approach. Additionally, PFE joined How2Recycle at the reclaimer facilities for the opportunity to learn and add project value. PFE is a candidate test lab for Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) that has worked with APR to develop several of its testing protocols for plastic packaging.

Real-life bales of Store Drop-Off material were broken up and analyzed in three locations from different retailers across the country; the types of packaging formats and contamination in the bales were assessed. In two cases, that sorted material was recombined (reflecting real world Store Drop-Off material as a whole) and turned into recycled pellet. In a third case, that material was kept separated into three different categories based on format, and the material from each format was then turned into recycled pellet. In total, over 2000 lbs of material were sorted by hand in these bale sorts.

Similarly, an array of specific PE film innovations along with resin controls were sent to PFE for analysis. The innovations to study were selected by How2Recycle, but specific formulations of those innovations (ones earmarked for potential commercialization) were selected by a handful of specific How2Recycle members with an interest in learning more about PE film recyclability. Members provided the material and covered some of the costs of testing—How2Recycle funded the rest. These materials were pelletized and analyzed.

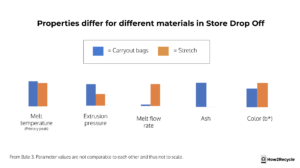

In accordance with the forthcoming APR Critical Guidance PE film test protocol, the material properties of all the pellets were assessed through many parameters, including: extrusion pressure (psi), delta pressure, delta from first to last 5 minute pressure, melt flow rate (190 degrees C, g/10 min, 2.16 kg), density (g/cc), primary peak melt temperature, secondary peak melt temperature, peak 1 enthalpy, peak 2 enthalpy, delta enthalpy, average ash %, % volatiles (160 degrees C), color (l*, a* and b* values), bulk density (kg/m3), pellet surface appearance, impurity content, and extrusion process irregularity.

The recycled pellets were then turned into molded parts. The mechanical properties of the parts were assessed through parameters according to the APR PE film benchmark test protocol (as the APR Critical Guidance test for PE film was not completed at the time of study), including: flexural modulus (psi), delta flexural modulus, tensile strength at yield (psi), delta tensile strength, elongation at yield (%), delta elongation, notched izod impact (ft-lb/in), delta notch izod impact, and melt flow rate (190 degrees C, g/10 min, 2.16 kg).

The pellets were also then blown into films. The processing properties of the film were assessed through parameters according to the forthcoming APR Critical Guidance PE film test protocol at 50% concentration, including: tensile strength (psi), delta tensile strength, elongation at yield, delta elongation at yield, tear strength (gf), delta tear strength, tear strength with thickness calculation, delta tear strength to 1 mil, impact failure weight (Wf), delta impact failure weight, impact failure weight to 1 mil, delta impact failure weight to 1 mil, process stability (y/n), film thickness, and a film appearance rating that assessed texture, gels, carbon particles/specks/unmelts, fisheyes, holes, and breaks.

The material was turned into pellet, parts and film because those reflect different ‘end applications’ for the material. How a material performs in different applications influences who will buy the material, and for what reasons. Additionally, different end applications highlight different qualities of a material, painting a full picture of its character.

In total, 9 samples of real-world Store Drop-Off bales were assessed, as well as 10 films representing 5 innovation types across multiple concentrations. The data points from all these lab tests were closely analyzed so that innovations and Store Drop-Off bales could be compared to each other. This analysis was supplemented by qualitative data gathered at the three on-site PE film recycler visits about buy/sell behavior, contamination, recycling processes and end markets insights.

While the study is formally complete, it is not over: learning will continue indefinitely into the future as the How2Recycle program, PE film recyclers and the packaging industry learn and adapt to evolving needs, markets and information.

Concurrently with this study, the Association of Plastic Recyclers developed its Critical Guidance test protocol for PE film recyclability. The work was informed by APR member company research in similar areas and used a consensus process to validate important features of the test protocol. APR was involved in several aspects of How2Recycle’s film study, including the film sorting and review of preliminary results. Input from the How2Recycle team was considered where appropriate in development of the test protocol.

How2Recycle is pleased that this work culminated in the announcement of the program’s adoption of APR’s Critical Guidance protocol for PE films (see detail in later section).

Key findings on the Store Drop-Off stream

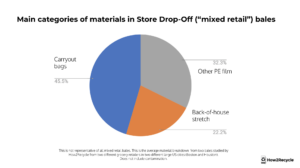

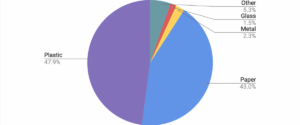

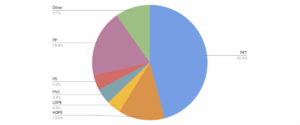

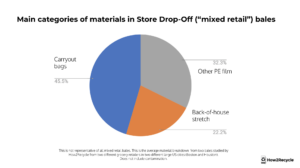

The Store Drop-Off stream is very diverse. There are many different packaging formats in it. The main materials seen in Store Drop-Off bales (often referred to as “mixed retail” bales) are:

- “Back of house” (predominantly LDPE stretch wrap from pallets in retail or distribution center operations), and

- “Front of house” (material from the consumer collection point at the retailer. This is where PE film labeled Store Drop-Off ends up; grouped with predominantly HDPE carryout bags, which usually constitute at least half of the front of house material).

PE film packaging from the “front of house” can take many forms, such as shrink film, case wrap, air pillows, ecommerce mailers, and pouches that may be HDPE, LDPE, LLDPE, ULDPE, or MDPE—either in monolayer or multilayer. This leads to a big variety of PE densities in the stream. Additionally, retailer and/or retailers’ employees’ behavior can contribute to variability in the material bale to bale within a location or across different retail locations.

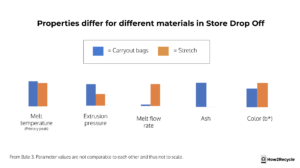

How2Recycle’s lab analysis confirms the big variety in PE densities: some of the highest and lowest values on the exact same testing parameter came from categories within current Store Drop Off material. For example, on melt flow rate in part testing, the lowest value of all materials studied was the carryout bags from the real Store Drop-Off bale, and the highest value of all materials studied was the stretch from the real Store Drop-Off bale.

PE film recyclers each manage this diversity in their own way: they may adjust their purchase behavior, and/or have different quality control processes in place, and/or may leverage certain equipment to achieve the desired density mix. How PE film recyclers manage the incoming material depends on the needs of their end application/s, such as density, cost, and various other material or processing attributes.

Most of the contamination in the Store Drop-Off stream is from items that don’t belong there, such as PET bottles and trash placed in the front-of-house retail collection bins. This is likely due to bin location (whether other recycling and trash bins nearby), or clarity/size of signage. In all three bale audits, there were no How2Recycle Not Yet Recyclable labels on flexible plastics in the Store Drop-Off bins. This suggests that on-pack labeling is likely effective in encouraging correct Store Drop-Off recycling behavior and in discouraging contamination.

In the back-of-house, the most contamination comes from non-film items such as hangers, pallet strapping and rigid plastics from deli operations. This is likely due to insufficient or inconsistent training of employees at the retail location, as well as possibly PE film recyclers not enforcing or struggling to enforce their own bale specifications.

While the samples studied are not exemplary of all or every Store Drop-Off bale, some common characteristics in the Store Drop-Off materials were observed. All samples showed a large percentage increase in extrusion pressure when creating pellet from the material. Carryout bags, in addition to having the “highest” performance of physical properties (this is based on recycler feedback that strength is desirable), it also carried the highest ash content. This is due to widespread presence of mineral fillers in shopping bags. In regard to melt temperature, there were observed secondary peaks for all materials. This suggests that material other than PE is in the Store Drop-Off bales because those materials have a higher melt temperature than PE. No stable runs (“process stability”) for film production at a thin gauge (30 minutes) were achieved for any of the variables in a lab setting, although film can successfully be made with this material at a thicker gauge. The existing Store Drop-Off stream contains various visual impurities.

Top: carryout plastic bags from Store Drop-Off in the form of ground flake; below: stretch wrap from retail back-of-house in the form of ground flake

Top: carryout plastic bags from Store Drop-Off in the form of pellet; below: stretch wrap from retail back-of-house in the form of pellet

Top: carryout plastic bags from Store Drop-Off in the form of molded part; below: stretch wrap from retail back-of-house in the form of molded part

Top: carryout plastic bags from Store Drop-Off in the form of film; below: stretch wrap from retail back-of-house in the form of film

Key findings on PE film innovations

Several PE film innovations were supplied, prepared, produced and studied at PFE: EVOH at different concentrations with and without compatibilizer, vacuum-deposited metallized PE, PE/PP resin blend, spunbonded PE (Tyvek), nylon, and nylon/EVOH blend. Each innovation film was blended with its control at 10%, 25%, and 50% concentrations to make into pellet and molded part, and blended with the same control at 50% and made into film.

While the ideal result of this study would have been to develop the ability to plot a variety of innovations on a spectrum of recyclability or provide confident guidance on maximum allowable percentages of innovations in PE films, How2Recycle is unable to draw sweeping conclusions about a broad innovation category (like EVOH) at this time. There are several reasons why.

Some innovations are better performing in recycling than others, but no innovation category studied as a whole is “definitely OK” for Store Drop-Off. Conversely, no innovation category studied as a whole is “definitely NOT OK” for Store Drop-Off.

Some innovations decrease the material properties as compared to their controls, but at varying degrees. Some innovations increase the material properties as compared to their controls, but at varying degrees. None of the innovations decrease properties on all parameters. None of the innovations increase properties on all parameters.

Some films studied showed better material properties as compared to the Store Drop-Off stream. Some films studied showed decreased material properties as compared to the Store Drop-Off stream.

When you increase the concentration of an innovation, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the impact from that innovation will be proportionate to the increase. In some cases the impact may not increase at all.

There can be notable variability of recyclability within an innovation category—for example some EVOH films performed better than others, when it was not immediately clear why. How2Recycle could not isolate the recyclability performance to the innovation for all parameters in all instances.

Importantly, How2Recycle learned that innovations cannot be analyzed in a vacuum: the film structure as a whole (including components like tie resins) impacts test results. It was not anticipated that tie resins would make a noticeable difference in the recyclability of the films, but they do appear to play a role.

When two innovations are utilized in a single film, the results can dramatically change (for worse, or possibly better in other scenarios). In other words, mixing innovations together creates a whole different beast. This is an opportunity for further study and innovation.

That said, in some instances observed changes may be attributable to the base resin selected for the film, not necessarily the innovation (see later section on test method).

It’s unclear to what extent the controls selected truly affected the end results, especially since the innovations were tested against different controls.

Because of these ambiguities, How2Recycle is recommending testing for innovations in PE film (see later section).

Looking at each innovation, mixed results were observed. Note that as only one or a handful of film structures representing each innovation were tested, these results do not speak to the overall recyclability of these innovations as a whole, but rather, the individual film structures studied. Accordingly, readers should not conclude that since a film studied possessed certain characteristics in testing that other films with that same innovation would perform the same, because this data set is limited.

For the PE films containing EVOH, secondary peaks were observed with a range of 165 to 182 °C. It was visually noticeable that the film production benefited from the presence of a compatibilizer. Still, none of the PE films with EVOH studied met all the test requirements at the film stage—but the melt temperature of the control, the type and quantity of tie resins, and the quantity and mol% of the EVOH appear to contribute to these results. Compared to the current Store Drop-Off stream, most but not all of these films showed decreased tear strength for the thickness correlation values and impact failure weight, with some slight negative film appearance effects, but these results varied for each EVOH innovation film.

For the metallized PE film, the pressure delta (in pellet testing) and tensile strength (in film testing) did not meet specification per the APR Critical Guidance PE film test protocol. When made into film, this innovation did not experience process instability. Compared to the current Store Drop-Off stream, this film showed decreased tear strength and impact failure weight, with some moderately negative film appearance effects.

For the PE/PP film (resin blend, not multilayer), a secondary peak was observed in melt temperature, indicating the PP melt temperature (compared to the primary peak of the PE melt temperature). Consistent film production stability was not achieved throughout the run time, and did present holes. When the bubble was able to be held, decreased tensile strength and elongation at yield were observed. Based on insights from APR’s study of similar structures, the concentration of PP in the PE film likely impacts film properties. Compared to the current Store Drop-Off stream, this film showed decreased tear strength and some moderately negative film appearance effects.

For the PE film containing a portion of spunbonded film (Tyvek), the pellet met all APR requirements. The film met all the requirements except for dart drop and elongation at yield. Compared to the current Store Drop-Off stream, this film showed decreased tear strength and impact failure weight, with some slight negative film appearance effects.

For the nylon films, the pellet met all APR requirements except for an extremely high and concerning secondary peak (compared to all other innovations studied and the Store Drop Off stream itself) in the range of 212 and 232 °C. These films had significant issues in blowing the film properly, leading to How2Recycle being unable to assess its characteristics.

The innovations studied did not meet the APR Critical Guidance test specifications.

Interestingly, all innovations increased tensile strength and elongation at yield in film production compared to the Store Drop-Off stream. All innovations decreased tear strength and impact failure weight compared to the Store Drop-Off stream.

As indicated, various concentrations of each innovation were studied, and this did provide different insights. The concentration of the innovation does change the results most of the time—but not always. That said, when you compare 25% innovation values to 50% innovation values, the value does not necessarily double. Sometimes the difference in performance between 25% and 50% is only extremely slight. Some innovations fail on a parameter across all concentrations. Other innovations only fail at 25% and 50% or at 50% concentration.

The nylon films did perform visibly ‘worse’ than the other innovations, but the rest were ‘near meeting specification’—with one EVOH film clearly ‘in the lead.’ They all nearly were in specification, in different ways.

The films studied are not vastly different from one another in the big picture. However, they do present marked differences when studied closely in comparison. While no one innovation in isolation would be catastrophic, these innovations are cumulative and need to be evaluated with that in mind. How2Recycle feels enough concern from these noted ambiguities that there is insufficient confidence to justify widespread R&D; guidance. Nothing How2Recycle studied is clearly “definitely OK”, and nothing is clearly “definitely not OK.”

If companies optimize the use of innovations relative to performance and recyclability in the R&D; process, all films studied stand a chance at Store Drop-Off recyclability.

What did How2Recycle learn about the test protocol design?

The selection of a control can certainly influence test results, because many parameters depend on the change between the control and the innovation (delta variation) not being too great. For example, if an innovation is known to increase tensile strength but a control is chosen that has relatively weak tensile strength, then the innovation will “look bad” because of a bigger delta between it and the control. In other cases, a ‘higher performance’ control resin can obscure the characteristics of the innovation, making it difficult to draw conclusions.

That said, not all negative or positive results are attributable to the selection of the control. How2Recycle was able to review the control chosen to understand some of the results observed (via density). Results were also compared to the data gathered on the existing stream to draw additional observations.

How2Recycle cannot compare every aspect of an innovation to the Store Drop Off stream cleanly, however. This is because many test parameters require the use of a control. The Store Drop Off stream does not have one single control. Recyclers also have their own novel purchase behaviors and quality control processes in place to segment feedstock by density depending on end application or other factors, and often mix Store Drop-Off material with “back of house” post commercial stretch, so judging innovations against the averaged qualities of the existing Store Drop-Off stream may not be appropriate in all instances.

Different recyclers may have different opinions on the relative importance of different parameters and how much change in a certain parameter (delta) from the control is desirable. Still, a delta is a good sense of how much an innovation changes the PE resin; therefore, How2Recycle feels this is the best available approach today.

Key takeaways

The quality and quantity of data gathered about certain PE film innovations is insufficient to create cutoffs or prescriptive R&D; guidance on specific film attributes. For certain PE film innovations, testing will be required.

Due to the insights uncovered by this study, as well as anecdotal or other evidence gathered in this process, How2Recycle has identified that greater understanding of these packaging attributes and their potential impacts to PE film recycling is desired:

- Cross-linked

- BOPE

- Tie layers

- Adhesives

- Sealants

- Ink systems

More data about these attributes will clarify the true cruxes of PE film recyclability and enable the development of more industry R&D; guidance. Companies are strongly encouraged to share test results of PE film structures with any of these attributes with APR to facilitate the expansion of the APR Design® Guide for PE film, as well as with How2Recycle to enable better guidance for future Store Drop-Off recyclability.

Moving forward: How2Recycle will adopt the APR Critical Guidance PE film test protocol

How2Recycle is pleased to announce that learnings from this work now enable the program to adopt a transparent, data-driven test protocol for Store Drop-Off recyclability: the Association of Plastic Recyclers’ (APR’s) soon-to-be-released Critical Guidance Protocol for Polyethylene Films.

In order to be eligible for a Store Drop-off label, testing will be required for PE film packaging with certain attributes (detail in later section).

Over time, the How2Recycle program will grow in its confidence (from increased amounts of data) over what constitutes an ‘innovation’ for purposes of requiring testing. The goal is to increase understanding over what variables are the true influencers of recyclability so that over time, less testing is required.

Why did How2Recycle select this test protocol in particular?

How2Recycle acknowledges that the APR Critical Guidance test is a high standard to assess Store Drop-Off recyclability. Still, the program has concluded it is the most appropriate test standard for a variety of reasons.

Most innovations “show their true colors” at the film stage. In other words, materials often (but not always) look similar to each other in the pellet or part stage but look fairly different at the film stage (when How2Recycle dramatically increased its understanding of how these materials behave). This was very apparent during the many months of testing at PFE, for both How2Recycle and APR. It is also more challenging to make film from a processing perspective than it is to make molded parts. This helps tease out the true potential issues of a material.

This is a young stream that the packaging industry needs to better understand. The APR Critical Guidance test gathers a lot of information that increases collective understanding. It looks at around 45 parameters across a control and various concentrations of the innovation. This allows packaging companies and recyclers to understand a thorough picture of an innovation with this many data points.

The test was developed in a transparent and collaborative way and the protocol is publicly available. Additionally, the test design is modeled after other extremely well-established plastic recyclability tests such as the APR Critical Guidance test for Clear PET Bottles, HDPE Containers and Bottles, and PP Containers.

Increased amounts of information that industry will be able to gather about how films perform under this protocol will help develop the APR Design® Guide for PE films over time with scientifically credible data, which will benefit the packaging industry as a whole.

The APR Critical Guidance test was developed and validated by a committee with PE film recyclers and material scientists at North America’s largest and most sophisticated trade association for plastic recyclers.

How2Recycle’s film study and APR’s validation work have demonstrated that the test design fundamentally makes sense, and it has been adjusted over time to take new learnings into consideration. For example, an increase in certain properties beyond 25% delta is no longer considered a fail of that parameter based on APR studies.

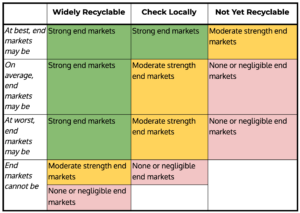

Store Drop-Off material currently goes into a variety of end applications, so a test protocol must contemplate those applications. Composite lumber and plastic bags are the current predominant end applications. Publicly available figures differ about the relative volumes of material going to those different applications so How2Recycle must consider both in determining a test standard. These applications require different material qualities. In many but not all parameters, a bag application is more demanding than a composite lumber application. For this reason, if How2Recycle ‘set the standard’ at the ‘lower’ quality level, then the material may struggle to meet the needs of the ‘higher’ quality level required by film applications. How2Recycle has no evidence suggesting a material could meet the APR Critical Guidance test specifications but fail simpler melt temperature and melt flow rate requirements for a composite lumber application.

Due to the increase of corporate carbon reduction and recyclability goals, more consumer packaged goods are moving into PE flexible packaging. Given that the Store Drop-Off stream is the only recycling option for PE flexible packaging at scale in the United States, this means that more product categories will move to PE film, which requires new packaging innovations. It is important that these innovations do not negatively impact the quality of the Store Drop-Off stream as the stream grows. Because the volume of Store Drop-Off material will increase over time, and the performance characteristics of the packaging will also increase to meet the needs of new product categories, it does not make sense to use a ‘lowest common denominator’ standard for the recyclability of PE film.

There is a need for stronger end markets for this material, as well as more diverse users of this material, and this test will support that goal. Shifting export conditions and other factors make this stream more fragile than other more mature recycling streams, so a cautious approach is warranted. Recycling streams are healthier when more recyclers are competing for the material and developing innovations for different end applications. If the material in the Store Drop-Off stream is sufficient quality to enable that material going back into film applications, this will help build end markets for Store Drop-Off. How2Recycle does not want to give a potential future PE film recycler or a buyer of recycled PE resin a reason to disqualify Store Drop-Off material because it is not of sufficient quality. How2Recycle encourages more recyclers to enter the space to maintain the viability of the stream long term.

What does this mean for How2Recycle members?

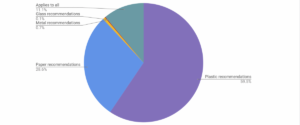

In order to be eligible for a Store Drop-off label, testing will be required for PE film packaging with these attributes:

- Forms of PE/Conversion methods

- Functional layers

- Metallized

- Nylon

- Nylon with compatibilizer

- EVOH

- EVOH with compatibilizer*

- PP

- AlOx

- SiOx

- A combination of more than one functional layer

- Attachments

- Rigid PP attachments (zippers, etc)

*Some structures containing Dow’s Retain technology are prequalified for Store Drop-Off.

At this time, testing must occur at a third-party APR candidate lab. How2Recycle will begin accepting test passes as soon as the protocol is released on APR’s website under “Test Methods” in the APR Design® Guide. And as included in the table above, metallized PE films will be required to undergo an additional test: Evaluation of Sorting Potential for Plastic Articles Utilizing Metal, Metalized, or Metallic Printed Components.

Important: as a result of learnings from this study, additional PE film structures may require testing in the future. Greater understanding of these packaging attributes and their potential impacts to PE film recycling are desired:

- Cross-linked

- BOPE

- Tie layers

- Adhesives

- Sealants

- Ink systems

PE films containing the following are acceptable for Store Drop-Off:

- Various PE densities including:

- ULDPE

- LLDPE

- LDPE

- MDPE

- HDPE

- Workhorse additives per the APR Design® Guide including:

-

- UV stabilizers

- Nucleating agents

- Antistatic agents

- Lubricants

- Pigments

- Impact modifiers

- Chemical blowing agents

- Mineral fillers (CaCO3, TiO2), assuming the filler does not cause the PE film to sink in water because of altered density.

PE films containing the following are Not Yet Recyclable:

- Biodegradability additives

- RFID tags

- Black PE (pigmented)

- PVC and PVDC

- Foil

- Certain applications:

- Food, beverage, personal care, or home care products that are wet, moist, sticky, gooey, oily

- Any products that are hazardous or potentially hazardous, or dirt or dirt-like

- Or any other similar product where it would be difficult or unreasonable for the consumer to prepare as “Clean & Dry” before recycling via Store Drop-Off (e.g. would require scissors to cut off fitment to rinse the inside).

How2Recycle provides recyclability assessments for every package featuring a label, so members do not have to conduct this analysis themselves. The way it works is members send the program detailed packaging specifications, and a custom How2Recycle label is issued. If testing is required in order to receive a Store Drop-Off label, the member will be notified by How2Recycle. If you would like to learn more about the recyclability of your packaging and transparently label it for end-of-life, consider How2Recycle membership. Contact how2recycle@greenblue.org for more detail.

How2Recycle would like to sincerely thank the following organizations for their support in this study: the Association of Plastic Recyclers, Plastics Forming Enterprises, Nova Chemicals, Procter & Gamble, Dow, General Mills, The Recycling Partnership, PAC Worldwide, Avangard Innovative, Novolex, Plastics Industry Association, Trex, Sealed Air, Amcor, and Printpack.

Questions, feedback? Please reach out to how2recycle@greenblue.org.

If you like this resource, you may like:

Design for Recycled Content Guide

Recyclability Insights

The How2Recycle Guide to Future Recyclability

This report, the information contained herein, and the images are authored and owned by GreenBlue, the parent nonprofit of How2Recycle. Any copies, derivatives, references or uses of this work must be attributed to How2Recycle with a URL link to this page.